a framework for giving a shit

choosing faith, of a kind, in 2026

While I have you: we’re starting out the year with over 13,000 subscribers. It’s good to have you all here! If you could take a moment to let me know, in the comments, what you would like to read about over the next year, it would help me understand you better and make sure I’m not boring you to death. Or, at least doing so more knowingly.

God is back, apparently. I’m not saying this because I just watched Conclave; the last year saw a ton of (potentially spurious) articles claiming that people were going back to religion, and whether or not these are Big Deity propaganda, it’s something I have noticed in my own life, too—people more opening discussing going to church, or mosque, or synagogue. God not as a figure of mockery, but as a serious idea, a presence in a modern life, a place to go to.

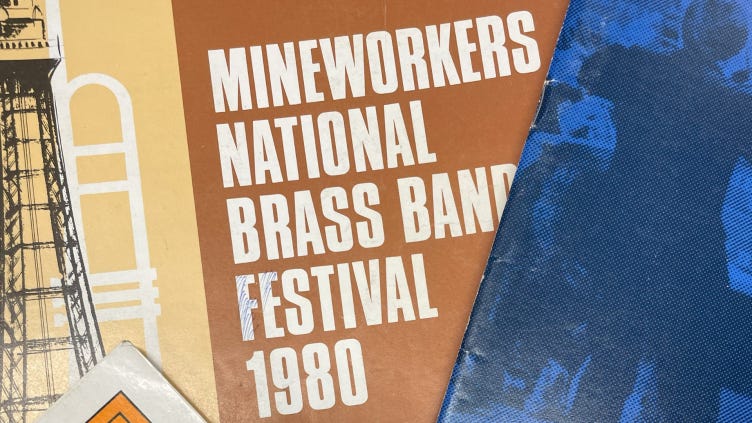

You can see why. We have, in many ways, spent 40 years completely destroying all our traditional avenues of community, and not just through the advent of invasive technologies that have convinced us all that the real people live inside our phones. Back in South Yorkshire over the festive period, I went with my family to the Grimethorpe Colliery Band Christmas Concert. I mentioned this to a few people (I had a wonderful time, the love of a brass collective hard-wired into my Yorkshire genes) and was surprised to find that many people hadn’t even heard of the concept of a colliery band. For the uninitiated, these were the brass bands formed by miners at many working coalmines in the 19th and 20th centuries. There was an enormous amount of pride in a pit’s band, and there was a huge culture around them even as Thatcher swung her scythe through the industry, most notably portrayed in the movie Brassed Off. If you want a pure slice of 1980s culture, watch the Grimethorpe Colliery Band performing a brass adaptation of The Eve of War, from Jeff Wayne’s War of the Worlds (itself adapted from the H.G. Wells novel), as part of the Champion Brass competition, broadcast on BBC North West.

My point is that we used to have culture and community surrounding jobs, even as we were ‘modernising’ those jobs, those communities, out of existence. People were encouraged to use and hone their skills, to engage in artistic pursuits, to spend time together creating. During the Grimethorpe concert, the bandleader took the time to praise his players, took the (gentle) piss out of one of them for his new relationship, pointed out the family members that certain musicians had in the audience. Just as moving as the music was the camaraderie and care these (mostly) guys had for each other. These days, none of the band work in the horrific conditions of the pit, but the strong bonds remain from the era of that work. They spoke about the material conditions of their current work and their financial struggles, the spirit of collective action still alive. My overarching sense is that things like colliery bands have not really been replaced in modern workplaces, especially not in the realm of hard manual labour.

This kind of community has been eroded since the time of Thatcher. All my life, it has been taken apart. The end of the 20th century was, in the grand scheme of things, a particularly godless, community-less time, the neoliberal order having neutered most outlets for human connection as it destroyed the idea of society altogether, then tried to force its rebirth as something that required a lot less government spending and social welfare and a lot more free labour from the proletariat (see: David Cameron’s Big Society).

We are finding now, a quarter of the way into a new century, that this lack of social fabric isn’t working for us. Having kids is a good way to disabuse yourself of the notion that there’s no such thing as society, but what about the rest of us? Tech capitalism has continued to isolate us from one another, to put up walls between us; we scroll endlessly on people’s worst ideas or most performative posts before publicly bitching about them for no reason whatsoever. We are desperate for connection yet only let people in based on a handful of self-descriptors, or a few photos on an app. We engage only insofar as we have already vetted people. When we do find connection, the messy humanity of it is a challenge: we try to police their behaviour based on a series of infographics fed to us by algorithmic design or according to sociological scaffolding we’ve decided upon alone, and when people fail to meet these completely inhuman standards we either robotically inform them of their failings (parroting those instagram posts that read like they’ve been written by psychopaths) or cut them out completely. We have grown unused to normal human interaction, both with strangers and with friends.

So what better then, than remembering there is a place where people of all backgrounds and jobs and experiences and energies come together regardless of whether or not they think they’ll like each other? A place where there is always community, always someone who will listen? I am not a person of faith, not at all, but even I can see what a house of god offers in the modern world (also: there was a bar inside Sheffield Cathedral for the Grimethorpe concert. You can get gigs and booze now at church, it seems). I can’t speak to what people get from their sense of faith, what it feels like to have a relationship with God, but on my more hopeful days I think that what people want is to actually give a shit about each other, and religions, in their most positive forms—like unions—give us a framework for that.

But what for the unbeliever? In the last decade, the secular, terminally online version of this framework has come from influencers—not the type posting photos from rented private plane sets or constantly filming their non-consenting children, but those who speak directly to camera on every topic available, who post in response to every political microstep, who spend a lot of time policing what everyone else dares to say online. Those whose primary job title seems to be activist, with little concrete to shore up that claim.

It is easy to see how a person gets into such a position. Most of us—at least, my generation and those coming after—grew up online. We rushed home from school to ring up enormous bills using the house computer to get On The Internet before our parents came home from work. We graduated uni into the new world of Facebook. We have adapted to new platforms as they have risen and died, learned to speak the language of Content. And then we got stuck there. Previous generations, when they were young and full of rage at the system, joined a bigger, already established movement, or learned from older people in real life how to agitate, and formed their own. These movements had already been or were immediately tested against real life, and were judged on whether or not they created material change. Coming of age politically requires you to have all the arrogance knocked out of you while learning to channel your energies into something less based on ego, and this process used to happen within the company of real people. Now, ego is a currency of its own; you need not be brought down a peg or two from your high horse and forced to prove your political worth. All you need to do is convince people on social media of how right you (theoretically) are. Whether or not your theories can be applied realistically is moot; what matters is not the real-world application of your methods, but how they make people feel. And when people feel disappointed or despondent, bitchiness is successful; public bitching about another project, another person, is a cheap win. If your primary job is to Post Politically online, you are judged on your visibility, not the effectiveness of your strategy.

The issue is that people with political influence used to have a hard-won moral authority. They had spearheaded movements, organised effectively, created change. They had risen through the ranks of the workers, stood up to and successfully subverted power, had sacrificed something of themselves in real, material ways for the benefit of others. They had provided for community, not just theorised about doing so. It is one thing to read about and appreciate the People’s Free Food Program, as instituted by the Black Panthers, and its quite another to have actually done it. Now, you can amass a following based on how well you can splice together a short video, or typeset a snarky comment. It is how we have ended up with such ‘activist’ advice as post a black square on instagram for racial equality. It is how we have ended up with posting as political activity.

Of this, we are all guilty. I do not mean to point the finger, except at a group that includes myself. That we have arrived here is not the fault of any individual; it is the fault of a series of technologies that know how to exploit human tendency, a laziness born of social disenfranchisement. But nevertheless, we have to see this for what it is: a performative politics, stuck in the realm of performance. Untethered theory is easy; if a political claim will never be assessed by its ability to successfully affect the material world, then you can just say any old shit. Discourse is never-ending, and largely pointless. If your political activity, your theorising, is all based within and on the world of social media, its assessment of how power works is one trapped in that realm. It so often does not meet the real world well.

And yet its inability to affect the real world is hidden. Its failure is quiet, invisible. The status quo is for nothing to change, so when strategies that claim to create change do not succeed, their lack of success gets washed away with the tide. The loud continue to be loud, the visible continue to be visible. The things they have said in the past get drowned out by the relentless posting, the unending performance, and nothing every changes, but we all feel engaged. Sitting in our homes, alone, doing nothing, we all feel engaged.

Like those going back to their mosque, or their synagogue, or their church, in the latter part of last year I got off my ass and went to join people who believe what I believe.

It was a small congregation, in a community centre in my neighbourhood. I said very little, and learned a lot. It was part of a much bigger political project, but it was self-starting and self-governing. It was imperfect. There was disagreement. There was frustration. But there were a lot of voices, a lot of history. Most people in the room were engaged in effective movements within their own realm, community or expertise. I shut my mouth, and tried to work out how best I could be useful. I will be going back, encouraging people in, and focusing on how best to create real change as a part of this project. I will try my bit to add to the framework we’re building, the one that might lead us all to a better, more equal, more fair way of living. A society that cares deeply and provides for all, rather than squashing those at the bottom for the benefit of those at the very top.

A church, a mosque, a synagogue—these are all fine places to go. They are fine places to spend time together, to be considerate, to care about other people. Like the harshly-lit room in the community space in my neighbourhood, they are also all political spaces. We engage in religion politically and culturally, as we engage in anything else. Sit two believers next to each other and you’ll find very quickly that there is not one way to engage with a religion; the ways we interpret and practice them are as unique as our fingerprints. We chose our places of worship based on what they preach, what parts of our religion they choose to emphasise, and the scaffolding they give us for how to engage with those around us. We test these frameworks against real life. They are not theoretical, but practical. Love thy neighbour. Love your fellow as yourself. Love for your brother what you love for you.

In 2026 I am choosing to have faith. Not in a god, but in my fellow citizens. I am choosing to get down and dirty with imperfect projects, full of imperfect people, with whom I will almost certainly, at some point, disagree. I am choosing community, as it really is, not in its ideal form only, but in the form of people who share work with me, or share space with me, or share the same hopes for the future that I have. I am choosing discomfort, and its potential to create change. I will listen more than I speak. I will resist the urge to public snark against people who stand only an inch away from me. I will look at how power works, and ask myself if the things I’m being asked to do will realistically achieve anything; if not, I will suggest an alternative, will risk being stupid and wrong. I will be okay with being told I am wrong. I will commit to a project, learn from those more experienced, use my skills where I can, assess what I’m told against my own morals, and most of all, act. It is time to get amongst each other, whether that’s in the house of god or a cheaply-painted room in the back of a public hall, and do something other than post.

thank you for the kick in the ass so many of us (me included) need 🫶

Heather, thank you for this wonderful meditation on the need for community. For me, this community can also be something we carry with us the moment we step outside of our homes, in the smile we present to the world, in how we answer when asked a question, in how we listen, and how we choose to respond. I just wrote a piece on my own community in North-West London that grew around a small city park, offering the kind of communion found in spiritual and religious communities: https://munakhogali.substack.com/p/ode-to-the-grange