Two weekends ago I went on something of a pilgrimage to Haworth, West Yorkshire, to the former residence of Emily, Charlotte and Anne Brontë. Despite being born and raised just an hour away, I had never visited Haworth, never before thought of going to the Brontë parsonage, where the girls were brought up by their clergyman father Patrick after their mother Maria’s death. A month ago I released a novel which owes much to Jane Eyre, featuring, as it does, the quintessential gothic ‘madwoman in the attic’ (though in my version of the narrative she has gone there seemingly willingly, in order to meet her mother’s pre-marriage demands); the influence of Jane Eyre on this book has been raised in interviews, but no one has made the connection that the Brontës and I—all women writing gothic fiction—were all raised in the same landscape, in the same county. Even I had barely thought of it.

I don’t remember, as a child or a teenager, ever being encouraged to think about writers from Yorkshire; only last month did I find out Ted Hughes went to the same high school as my dad. This may be because writing was not seen, in Rotherham, as a thing that someone could do, as an actual job. I remember being told at a careers meeting that I might become a teacher or a politician (the latter no doubt because a Rotherham boy, William Hague, was Leader of the Opposition at the time, and also because I was a highly opinionated youngster), but never was an arts career mentioned. Why would it be? The only person my family knew in an arts-related job was a local photographer, for whom my mum briefly worked. Rotherham is a former coal and steel town, one of those places from which heavy industry was pulled, by Thatcher in the 80s, to be replaced by a sea of call centres and retail parks. Back before the Millennium, the creative industries seemed to happen somewhere else entirely, the arts done by people other than us.

Only a year or two before this careers meeting we’d been taken on a school trip to see Simon Armitage perform. I remember being stunned by this, by the idea that someone who had such a broad Northern accent—not even someone from Yorkshire, just someone from north of the midlands—could be performing on stage. This was a handful of years before the Arctic Monkeys and the indie sleaze/pop movement of the early 2000s made it not only acceptable but actually cool to speak like you were from Sheffield/Leeds/Liverpool/Newcastle. Earlier this year, it occurred to me that the Brontës, too, must have had Yorkshire accents, mixed with a little of the Irish with which their father, Patrick, spoke. Still now, I can’t really imagine the sisters reading out passages from their works in progress with flat vowels and glottal stops in place of definite articles, the past being a prism through which we erase such markers of identity.

I booked myself a night in a B&B on the Main St in Haworth, keen to not only visit the parsonage but sort of mill around in the general Brontë milieu, as much as is possible at a 200-year remove. I thought it would be much more touristy, but it is like a better-kept version of a hundred other village high streets; a coffee shop that gestures towards decent coffee but never quite achieves it, a couple of second hand bookshops, a handful of places selling local crafts, a few pubs. There are two good restaurants, one which books up months in advance and the other in which I sat reading the new Paul B. Preciado book with two glasses of wine over lunch, chatting to the waiter about it afterwards. The table next to me ordered several plates of truffle fries which were so pungent I almost moved, but didn’t.

The Brontë parsonage is like a reverse Tardis; it looks much bigger from the outside. There’s a quiet grandeur to it from the street, then once you get in, you realise that the heavy stone walls have not left much space for the actual rooms. To imagine Patrick, another adult and six children inside—not only Emily, Charlotte and Anne but their brother Branwell and two older girls, Maria and Elizabeth, as well as their mother, until her death, and afterwards their aunt—is to see a perpetual spillage of people from room to room, bickering and pushing and jostling for not just space, but attention too. But within that jostling, connections are made: the children’s imaginations intersecting, the characters and situations they loved to invent creating one vast and multifacted landscape within the shared mindscape of the Brontës. I thought of a conversation I’d had with a physicist years ago, about the idea that consciousness is in fact one giant shared entity that you all tap into: never your consciousness but our consciousness. In that house you can see the foundations upon which the girls’ tortured moors were shaped and built. You can see how the worlds of their books were created—or, perhaps more accurately, reflected.

The rooms downstairs contain some furniture, the minute kitchen kitted out how it might have been when the children were alive. Upstairs, the rooms in which the girls slept house glass-walled cabinets behind which lie their belongings: their paint sets, their clothes, some pages from their notebooks. Everything is presented at a distance, labelled as in a museum. Patrick’s bedroom contains a bed and other furniture, to show how the head of the household might have kept his only private space. But it is far from lived-in. Even the nursery next door has its vague doodles, ascribed hopefully to the sisters, constrained behind glass.

Then, you step into Branwell Brontë’s room. A marked difference from the rest of the parsonage, this room looks as if its former resident had only stepped out for a moment, with its unmade bed, its screwed up, scribbled-on papers. This room, much more than any of the others, invites you to imagine the person within it as a person, a living breathing entity, someone defined not by what they produced but by the fact that they were engaged in the act of creation, in living and breathing and thinking. In fact, the room itself is an art installation, created by none other than Simon Armitage; the ‘exhibition’ is entitled Mansions in the Sky: The Rise and Fall of Branwell Brontë. It presents poems written by Armitage in tribute to Branwell (one of which refers to a Smiths song in its title: William, It Was Really Nothing). Easels and frames lie propped against walls, books are piled high, sketches and poems and skulls adorn every surface. It is the most vibrant, living space in the parsonage; a monument to creative vision, to a troubled and brilliant creative mind.

The issue here, of course, is that Branwell Brontë may well have been troubled and he may well have had the makings of talent, but the brilliant minds of the Brontë parsonage belonged to the three women who made it to adulthood: Emily, Charlotte and Anne, without whom this building would just be another clergyman’s house, without tens of thousands of people visiting it each year, drawn by the enduring legacy of Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. And yet we do not get vivid installations for Emily, Charlotte and Anne, imagining their deep and tormented inner lives, their griefs and their hopes and their struggles and joys. We get the dress that Charlotte wore to meet William Makepeace Thackeray, or the “pretty rings” she wore to show off her “small and delicate hands”.

Much is made of the central role that Bramwell (may have) held within the fleet of Brontë youngsters. There is a often-repeated story in which Branwell was gifted a set of toy soldiers and shared them with his sisters, leading to each one naming their soldier and using them to write stories (Emily’s soldier was called Parry, a fact that tickled me excessively). Even Armitage, in promoting the installation, told the Guardian that Bramwell “was driving the whole show.” But it seems obvious that it was the fact of Branwell’s maleness that created this situation. Branwell shared his soldiers with his sisters precisely because he had been given a set; the girls had not. He was given authority over his sisters precisely because he was the only son. It was Branwell that was sent to the Royal Academy in London, not his sisters, and it was Branwell that, we assume, failed to get in (he did not attend). The five girls were sent to a clergyman’s school with conditions so poor that two of them caught TB and died; the others held, throughout the rest of their too-short lives, that their time in the typhoid-ridden school had affected their health permanently. But it is Branwell’s health, his thwarted promise, his wild and intense mind that the parsonage visitor is invited most keenly to consider. Perhaps, as Daphne du Maurier lays out in her biography The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë, the Brontë brother’s case is a tragic one, of squandered talents and unfulfilled potential. The sadness of this is noteworthy, of course, as are the much less-considered deaths of Maria and Elizabeth, who never got to find out what they might be capable of. But why must we always—and in this case, egregiously, given the context—position the potential achievements of a man over the actual achievements of three women? Whatever Branwell Brontë might have done, his three youngest sisters actually did—and without the advantages that their brother was given.

Perhaps to most visitors, the difference in how the Brontës are presented is not so stark, but for female writers, who find themselves critiqued and labelled very differently from their male peers, it is astonishingly obvious. In the days since my visit to Haworth I’ve raised this in front of an audience and to some friends, to find that many other women who have visited the parsonage have noticed this too; it is their most enduring feeling about the place, that Branwell was so highlighted and that his sisters were not. How depressing it is that women—some writers themselves, some readers and creatives in other forms—go to the former residence of three of our most celebrated female novelists and come away with the impression that no matter how much you achieve in life, no matter if your work manages to break through patriarchal barriers and change the canon of English literature forever, if there is a semi talented man nearby you you will always, in some fashion, be shown in relation to—and diminished by—him. As my brilliant friend

wrote, after her visit to the parsonage:I was left disheartened and baffled at the romanticisation. Why not use the same amount of imagination to recreate one of the rooms the sisters slept in? Sewing kits and writing boards splayed open, crumpled bits of paper, corsets and hairbrushes, a bed for Emily’s dog Keeper which she did a magnificent drawing of, or a room from one of their novels; broken bloodied windows, rancid meat, bowls of burnt porridge, sinister red curtains. There seemed to be discomfort in the fact Bramwell was nothing more than a muse to his sisters, and muses are arbitrary.

Too late in the day I decided to take a walk out to the waterfall that the family frequented, and, slightly further, a ruined farm building that was said to have inspired Wuthering Heights; a three-hour round walk altogether. The wind was already up and the clouds threatened, but I set off, trying to inhabit the conditions in which the Brontë sisters would have spent their days, to notice how the land itself influenced their fiction.

I didn’t make it all the way to the building, as it started to rain and I was wearing a wool coat. This is not an unusual experience, when heading out across the county’s vast lands: my entire childhood is marked by memories of being battered by a gale, or soaked through from unanticipated rain, or, worst of all, both. I remain an ardent hater of any kind of weather, so I scurried back to the nearest pub to dry off without even having seen the waterfall, let alone anything else. I did, however, find the feet of a hare and the bloody, matted remnants of its body, either crushed or eaten to torn apart by a fox or an owl or even a hawk. In my flat in Glasgow, I have the entire spine of a sheep, found vertebrae by vertebrae on a hike; you cannot go far into the northern countryside without encountering death, or evidence of it.

Camilla wrote, of the moors:

The landscape was brown and purple, like menstrual blood. It was one of the most beautiful things I had ever seen, both alluring and dangerous.

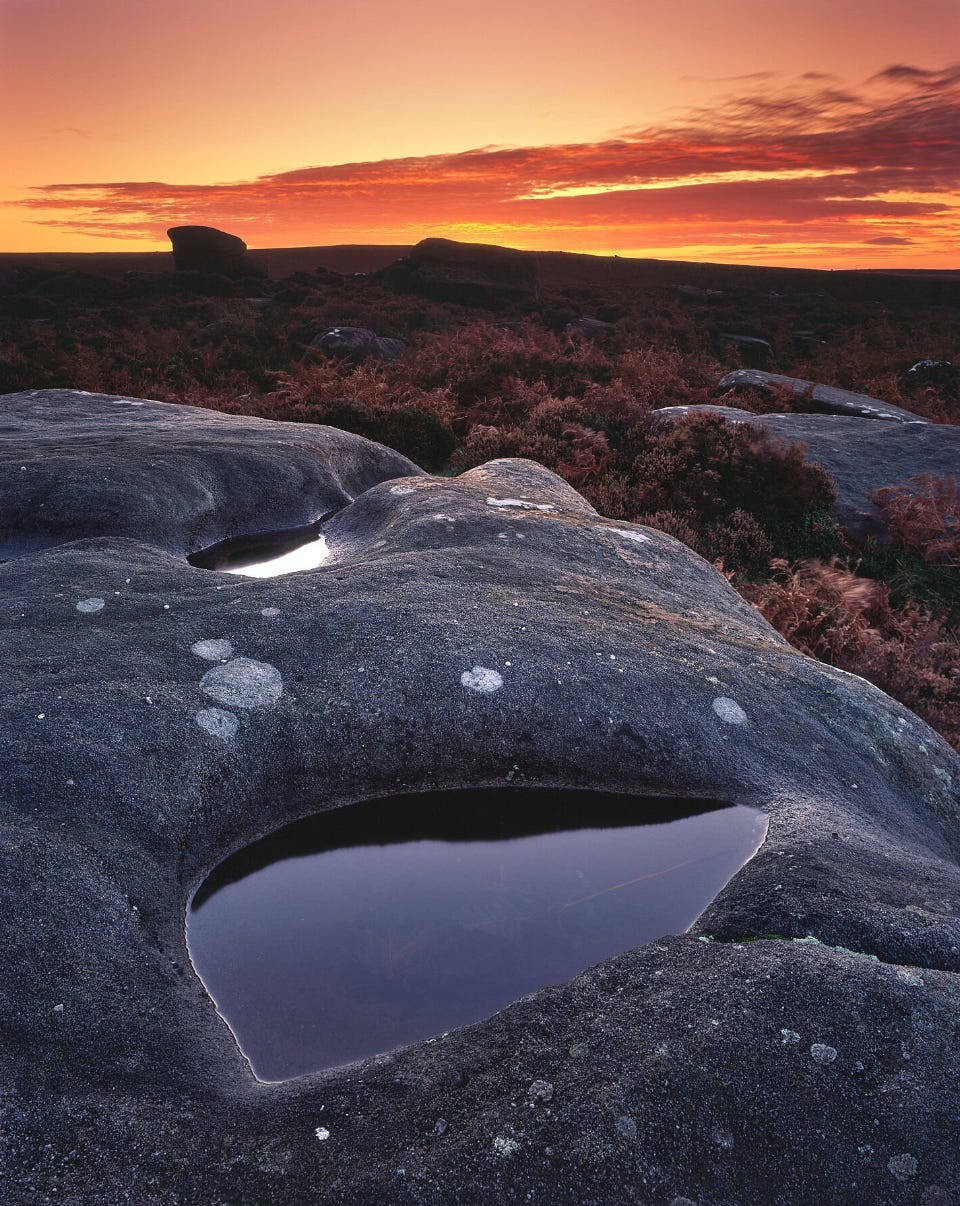

This is perhaps the perfect description of the landscape of Yorkshire countryside, the sort of thing that could only be formulated by someone who did not grow up in it. When I think of it, I think of immense stretches of green overlaid with deep purple heather, and the endless undulation of the land, its surface broken by jarring yellow and grey gritstone. As it creeps over into Derbyshire, over the north part of the Pennines, its sheer expansiveness, its exposure, makes it dangerous; when you pass through the Pennines all you can imagine, even on the most glorious blue-sky days, is being stuck out there in snow or rain or even the dark, or indeed the ease with which you might be buried and forever lost.

I have lost count of the times I have been making the drive across the Pennines with the windscreen lashed by the kind of rain that moves earth, or snow settling so quickly on the road that traffic slows to a crawl, even the most seasoned drivers beginning to sweat with the stress. In fact, the road on which you make this journey is constantly closing; currently there is at least one stretch where half of it has quite literally fallen away, and the relevant council is so tired of paying for fixes that the future of the road has been called into question. I feel weirdly emotional about this. It is my favourite drive in the whole of the country, one I have taken many times both with family and alone. The Snake Pass—the road we’re discussing, named not for its winding shape but for the Snake Inn, which it goes by— takes you from Sheffield to Manchester, the connecting stitch between the two fleshes of Yorkshire and Derbyshire; a drive that takes you through glorious views but also strikes fear into the hearts of those who were born near a functional road system, or who have lived their entire lives in a city, with public transport that gets them where they need to go quickly and reliably. Even without its landslides, it is known as one of the most dangerous roads in the UK, with—according to the rancid Google AI feature that I haven’t yet figured out how to turn off—“blind summits, hairpin bends, steep slopes, narrow passages, and tight bends”. I have spent so much of my life on this road, it is almost part of my personality. When I think of Yorkshire, of going home, I think of the Snake Pass.

At the other end of this road, just 45 minutes from where I grew up, is Glossop, where Hilary Mantel was born; she was raised in Hadfield, a five minute drive further. When Hilary was seven her mother moved her lover into the family home alongside her husband; four years later, Margaret moved the children to Cheshire, along with her lover, leaving both her husband and the scandal behind. When it came time to study law, Hilary went first to London then transferred to Sheffield, and when she had graduated in 1973 she returned to the other side of the hills, working at a department store in Manchester before moving abroad with her husband, then eventually down south for good.

So little is written about Hilary the northerner, Hilary the child on the cobbled streets of Old Glossop, Hilary the imaginative youngster, staring down into Longdendale Valley and breathing in the wide, clear air. I often wonder at this, because, to me, the place where Hilary spent her most formative years is inextricable from the writer she became. You cannot live in these spaces without them affecting how you see the world. If Emily, Charlotte and Anne had the ruined farm buildings and wide open fields of Howarth, the deaths of their two older sisters in a grand house ridden with typhoid and TB, Hilary had the menstrual moors, the imposing openness of the landscape, the Gorton home twenty minutes away from her own, into which Ian Brady and Myra Hindley moved; as her mother Margaret was moving the family to Cheshire, the first of the ‘moors murders’ were being committed, the bodies of the children buried on Saddleworth Moor, just eleven miles away from Hilary’s home. Things like these, learned of when you are at your most impressionable, your most malleable, forever shape how you understand the world around you, its threats and its shadows and the balance of dark and light. Hilary herself wrote about this in her later books about her own life, yet the culture seems adamant in underplaying its influence, perhaps because—as we are shown over and over again—the inner lives of women are only given due prominence as much as they can be neatly packaged into the shape of ‘feminine concerns’: fertility and parenthood, their childhoods, the family world. The most known thing about Hilary Mantel, outside of her work, is the endometriosis that robbed her of the chance of children. But this did not make her who she was. Women writers, even those who become parents, are more than this experience, but they are so rarely considered in totality. Everything else that has formed them must be downplayed, whether that is religion or race or politics or the land on which they grew. But you cannot diminish the landscape of a person. Even the names of these places are heavy with significance: Bleaklow, Hope Valley, Mam Tor (Mother Hill).

Last weekend I read raw content, the brilliant new novel from Bradford-born writer Naomi Booth. I have loved Naomi’s work for a long time, and this book is a departure for her, away from the high-concept, surreal-leaning novels and short stories of her time with Dead Ink. raw content follows a new mother, Grace, in the early days of parenthood, as she discovers that the landscapes and stories of her childhood in the Colne Valley—on the Yorkshire side of the Pennines—have affected her more than she ever realised before, plunging her into a postpartum psychosis. Peter Sutcliffe, Ian Brady and Myra Hindley are the ghosts that haunt Grace’s youth, but it is the land itself that remains pregnant with dread, the empty mills and the rushing rivers both poignant and alive. I read this part out to my partner over brunch, and found myself emotional:

We mind the cracks and say Amen after the school prayer. But at night, when the air rings, the valley is alive around us, baroque with threat – the alleyways, wasteland, woodland, canal paths, Saddleworth Moor, Dovestones Edge, the Boggart Stones – all the terribly beautiful places, where the wind moans and the earth keeps its dark secrets. We cling to the rules, in the daytime: but no rules can stop the dark energy of this valley filling our dreams at night.

In the Acknowledgements of raw content, Naomi writes that, amongst other writers, she is indebted to Emily Brontë. I wonder if the truth of it is that Naomi, Emily and I, as well as countless other female Yorkshire (and Derbyshire) writers before us, are indebted to the rainsoaked moors, the blankets of heather, the broad and open landscape which holds death and life together at the same time, forcing you to confront both.

Another glorious Sunday morning read thank you Heather. I grew up in the south of Scotland with it's mysterious landscape and dark history - both past and recent. I definitely resonates that it shaped my belief in the world being a dark, gothic fairytale (my Dad firmly believes to this day that Tolkien must have found his Middle Earth in the Borders!) so I found this piece quite moving & emotional.

I love and relate to this immensely. I'm from South Manchester and now live at the edge of the Peak District in Macclesfield.

I think you should send the Brontë museum this piece. Or have you already messaged them?