For the last year my partner has been studying for an MSc full time. Though this has been an incredible step, and a journey of growth for both of us, it has put various strains on our household—not least the difficulty of supporting two people (and a mortgage and two cats) off one writer’s income (through a cost of living crisis, sky rocketing bills and the double whammy of high inflation/widespread wage suppression) while also paying for education (an MSc is not free in Scotland, and loans don’t cover the whole amount). It has taken a serious joint effort, and still I have come out of it, and the five difficult years previous to it, burned out, exhausted, overworked. It doesn’t take the exact circumstances above to end up at this place; so many of us are these days.

When I’m stressed and overworked, the first thing that goes is cooking. I vividly recall a week in 2021 where we had Aldi vegan nuggets and peas more than once in a week, which is fine if this is your comfort food, but it’s not mine. For me it’s a signal that neither myself or my partner have the time or brainspace to put together a proper meal; it’s a sign that we didn’t have time to go shopping, or we’ve thrown away something out of the veg box because it went mouldy instead of being used. It’s a klaxon that things are being stolen or wasted: our energies, our time, our capacity for caring.

When my partner got accepted into the masters program, I bought several things: a new backpack, travel cutlery (proper metal), a flask in which you can keep meals hot all day. I was committed to sending D off to uni with a nourishing meal, to make the bleak winter starts not too bad, the cycle into the city not so gruelling, to make the learning come a little easier—not because it was my job, nor a gendered expectation, but because I am good at it and wanted to do it. What surprised me was how good this was for my wellbeing too.

I started to make chicken soup from scratch, roasting the bird, boiling down the bones and skin to make stock, adding celery and root veg and garlic and onions and all the meat that otherwise gets lost (I don’t eat meat, but if someone else is going to, I want them to eat it well, with no waste). I made borscht with minute steak, using up the avalanche of beetroot that arrived in our veg box over consecutive weeks. I made thick ragu, hearty curries, and soups and stews with neeps and potatoes and fresh dill and whatever else got delivered to our door with the changing seasons, trying not to let anything rot or soften. All of this meant long afternoons in my kitchen, dancing to music or listening to podcasts, filling the house up with the aromas of loving someone else, of putting effort into making them feel good. It slowed me down, it calmed me. It fed me.

It’s easy, and I think wrong, to say that cooking is inherently anti-capitalist. There are a million useless and highly-marketed gadgets you can buy for your kitchen, hundreds of ludicrously expensive ingredients to succumb to, a relentless churn of consumption without satisfaction that you can buy into around the production of food. What feels more correct to me is to say that slow cooking—taking your time, being thoughtful, reclaiming the pleasures of making a meal—can be a work of anti-capitalism. The writer Yas Floyer described it to me last week as an “act of resistance”. She took the words right out of my mouth.

What we resist by taking the time to cook is not the production of meals by other people—despite what unhinged online commenters would have you believe, the revolution will not ban restaurants—but the constant squeezing of our time, the capitalist notion that everything should be more efficient, more output-focused. That it is easier and better to buy things than to waste our time in processes when the outcomes can be bought cheaply, freeing up the rest of our time to work. The notion that we should work on evenings, on weekends, in the early morning; that the only worthwhile labour is to make something that can be sold, for our profit or the profit of the people above us. What we’re reclaiming is our time and effort, the pleasure of doing something for the financial benefit of nobody. As Michael Pollan puts it:

…in a world where so few of us are obliged to cook at all anymore, to choose to do so is to lodge a protest against specialization—against the total rationalization of life. Against the infiltration of commercial interests into every last cranny of our lives. To cook for the pleasure of it, to devote a portion of our leisure to it, is to declare our independence from the corporations seeking to organize our every waking moment into yet another occasion for consumption.

- Michael Pollan, Cooked

I don’t think its just the spending-conscious Yorkshire dad in me that loves taking a yellow-label whole chicken from the reduced section of a supermarket and spending a whole day making ten meals out of it, ten meals that I will not eat. I think there’s something in us that swells when we save something from being thrown away, when we take our energies and spend them towards needlessly creating something to please and nourish another person. When we take all the sad, turning veg from the bottom of the fridge and turn it into a soup to be mopped up with bread we have made, to the delight of someone we have chosen to love.

There are many people who won’t approach the kitchen in this way. They can’t; they have to provide for themselves and others efficiently, in terms of both time and budget. It’s hard to love cooking when you have to do it in the ten minutes before bed, after a night shift, or when you have to cook for a whole family, including children, several times per day; when the takeaway or the Tesco sandwich present a much better return on investment. Perhaps they don’t have a kitchen, nor food to cook in it. For them, meals are simply another obstacle to overcome amidst an endless tide of daily difficulty. But isn’t food something communal, something that we can all try to provide for each other?

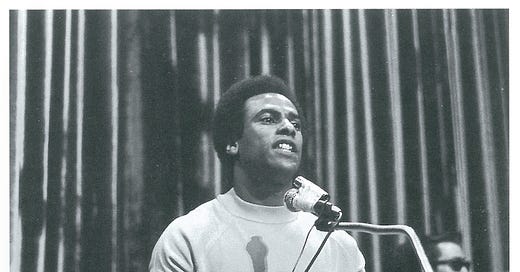

Anti-capitalist approaches to cooking have been at the forefront of resistance movements for a long, long time. A key part of the Black Panther Party’s organising was a their Free Breakfast for School Children Program, in which they went from feeding 11 kids breakfast in January 1969 to feeding 10,000 children across America by 1971. This was just one of the Black Panthers’ ‘Survival Programs’, the fleet of actions they took to provide Black people with what they needed as a way to resist the state’s violence against them, to allow them to thrive in the face of structural hostility. This thinking survives today in program’s across America, like Oakland’s People’s Kitchen Collective, and far beyond.

When I lived in Sydney, there was a small anarchist space in Newtown that made meals every Wednesday for whoever needed them. The cooking team was made up of volunteers, the ingredients gained via donations from local veg box providers and cafes, or through dumpster diving, the practice of saving perfectly good food from bins before they are tainted. Anyone could come and eat in this space; homeless people could come and share a hot meal with their neighbours, could be sure that someone would sit and read a book with or otherwise entertain their children while they both ate, giving them a tiny bit of respite in their parental responsibilities. The most vulnerable would be sent away with the leftovers, and as many snacks as could be rustled up. In the first lockdown, in Glasgow, a subgroup of our local community Facebook group was set up for volunteers, people who had time and energy to support their neighbours who were kept at home through medical vulnerability or disability or anxiety. So much of this was food-related; my partner and I made a huge stack of freezer meals for a mum who was trying to care for herself, a new baby and a toddler. We dropped the bag of Tupperwares off on her front step; we never even saw her face.

This was just one of a thousand such acts that happened throughout Glasgow in 2020, and continue to happen quietly every day. In this city, Food Not Bombs has a stand in my local park every Sunday, giving out free vegan food that’s been made from items donated from gardens and shops and cafes. There are community pantries that offer groceries at very low prices. There is a program to make meals for your elderly neighbours, to ensure they have a good hearty dinner, made by someone who cares. At the heart of these programs are people making food for others, just for the sake of it, asking for nothing in return. As filmmaker Roger Guenveur Smith said when he portrayed Black Panther Party founder Huey P. Newton in film, “nobody can argue with free grits”.

The term “self-care” has been thoroughly bastardised by capitalism in the last decade; it’s more easy to commodify than the alternative, which is community care. But community care is also self-love, because it resists the alienation that capitalism encourages; it reminds you of how good you feel when you do something for someone else, someone you might not even know or like or ever even meet. All of these movements, large and small, understand that making a meal for another person, and expecting nothing back, is one of the most radical things you can do—both for others, and for yourself.

There was something especially lovely about reading this in the queue for our weekend community bakery. I’ve started both shopping at and volunteering with some of North Edinburgh’s community veg gardens and it makes me feel so connected both to nature in general, but also to the area. It’s incredible that these places are just tucked away behind a pub or the Granton Gasworks.

Yes! I cook and prep meals for my family multiple times a day and though I love to be the one who can do this for them, there's no denying that when overwhelm from other quarters appears, it's the first thing to slide (provoking uncomfortable feelings of woe is me, too).

Then I beat myself up about the convenience foods that appear. The veg box tatties and broad beans I can't begin to concoct a new recipe for.

But those evenings when it's blissful in the kitchen and the shopping's been done... 6Music is on the radio, the candles are lit and there's something chilled in my glass.

Oh, then I LOVE preparing food. And eating it with the people I love.