The time has come, my friends. I told myself I would do it a year ago. I told myself I would do it at the start of this year. I told myself over and over again, and yet didn’t, because I fundamentally think that everything should be free in a perfect world. In this world, however, there are bills to be paid and cat food to be purchased—and as these essays settle at over 4000 words each, with research required and expenditure increasing, they take up more and more of my potential working time.

I’ve met tons of you in the last few months, at my book launches and other events, and you’ve said such kind things about your Sunday morning rituals reading these essays, and the things they’ve made you feel and consider. I hope that you see enough value in this writing to join me over the paywall; becoming a paid member starts at £4 per month, the price of one coffee. If this is beyond your budget, do drop me a message.

I won’t be promising you more content. You are busy people and you read a lot; the last thing you need is to hear from me more often. Your support does mean, however, that I can invest more in these essays; I can research more, travel more, commit more time to improving my thought. Free subscribers will have access to an essay once in a while, and a roundup at the end of each month.

However you continue your support—thank you for being here.

In February 1812, a young man, just turned 24, made his maiden speech in the House of Lords, three years after he had first taken his seat; like many young noblemen before him, he had headed for the continent, to continue his learning and repeatedly get his end away. By the start of 1812, his first big poem was quite literally at the printers; he was about to become famous, and would go down in history both as a poet and as the archetypal work-shy, romantic, sexually ambiguous cad, equally enamoured with appreciating nature and fucking people he shouldn’t have. How interesting, then, that when Lord Byron finally took to his feet in the House of Lords, he did so in strident defence of one of history’s most unfairly maligned group of workers: the Luddites.

If you’re at all involved with the labour movement, there will have come a time when you realised that the Luddites were not, as popular media would have you believe, a group of people completely opposed to technology or mechanical advancement, but a collective of highly-skilled workers who quite reasonably opposed both the loss of their jobs and the decline in quality work at the hands of mechanisation, and who responded by destroying the very machines that were being used to take away their careers. In fact, the Luddites were just the most famous actors in a long history of violent resistance by British textile workers, which dates back to the 17th century. Their beef was not with machines themselves, but with the employers who would rely on the machines, despite their poor-quality output, to save themselves money on labour and increase their own profit margins by laying off their workers, leaving the workers unemployed and impoverished.

At the start of the 19th century, it was the introduction of knitting frames to produce lace and shearing frames to finish wool that triggered violent response, as well as steam-powered looms used to finish cotton. Accurately predicting that the use of these machines would pose an existential threat to their skilled trade and their livelihoods, the highly organised Luddites agreed to embark on a campaign against them, of which the dismantling of the machines was just one part; public demonstrations and the petitioning of government officials were two others. They recognised that, as long as the profit-fetishising mill owners had access to the machines, their concerns would fall on deaf ears and their jobs would be under threat, their families at risk of destitution and death. So they exercised their power in the only way they could: destruction. As Lord Bryon put it, as he argued against the proposal of the death penalty for ‘frame-breakers’:

These machines were to [employers] an advantage, inasmuch as they superseded the necessity of employing a number of workmen, who were left in consequence to starve… These men never destroyed their looms till they were become useless, worse than useless; till they were become actual impediments to their exertions in obtaining their daily bread.

Even Lord Byron understood that no one hates technological advancement in and of itself, but only when it is an unwanted addition to their lives, diminishing what talented people can produce and usurping human labour for the betterment of nothing but profit margins. In short, when the human cost of it is too great, and when those who stand to benefit are not the people, but the wealthy few.

Perhaps, as a struggling poet (who had already ordered the destruction of his first own volume of verse, concerned at how its more sexually explicit portions might be received), Byron appreciated more than most that humans take a great pride in the productions of their labour when that labour is unalienated. Give them challenging work that tests their skills, space to be creative in how they express those skills and investment in the life of what they have produced—not only financially, but in knowing that their products will be loved and valued for generations to come—and they will feel great satisfaction. For textile labourers at this time, the quality of the product was not incidental; it was something in which they took great pride—so much so that Byron raised this issue, too, in the Lords:

By the adoption of one species of frame in particular, one man performed the work of many, and the superfluous labourers were thrown out of employment. Yet it is to be observed, that the work thus executed was inferior in quality, not marketable at home, and merely hurried over with a view to exportation. It was called, in the cant of the trade, by the name of Spider-work.

I have come to like this term, Spider-work. Perhaps, in Luddite terminology, such work was considered to be pretty but wholly unsuitable for purpose; a thin and easily breakable simulation of that created by real, skilled, sturdy textile labour. I like to think of it from a slightly different angle. An arachnid may create something beautiful in its web-weaving, but it does so not through any creative drive nor particular skill, but by chemical impulse, in order to murder other creatures for its own betterment. When a lowly fly is trapped in an intricate spider’s web, it is caught, injected with venom and immediately consumed. Spider-work might appear beautiful or novel, but its primary purpose is to trap, to drain for the benefit of the invertebrates who created it.

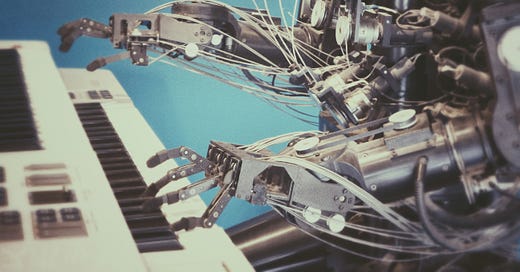

Yes, that’s right. We’re going to talk about AI.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to general observations on eggs to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.