‘Driven by bacteria that spawned all life on Earth and continue to be the matrix of all life, fermentation is a force that cannot be stopped. It recycles life, renews hope, and goes on and on.’

- Sandor Ellix Katz, Fermentation as Metaphor

A few weekends ago I was invited to a new friend’s flat for brunch. The older I get, the the more I appreciate the little bubble of bravery required to take that small step; to change a relationship from a distant one to something closer. This friend asked me to bring some fruit along, to complement the things he’d be making, and on calling in to our local shop I found that perfectly ripe, achingly sweet pineapples were on sale; I got two. After chopping up the flesh to serve, I left him with the peel and rinds and a recipe I love; on the way back I bought two for home, specifically for the rinds and peels. The outer shell of a pineapple holds the key to a little bit of magic.

When you become a fermentation nerd you start to appreciate that the natural world holds secrets; that the air we breathe and walk around in and agitate by our movement carries on it a huge range of substances that we can’t even see. Airborne microorganisms make their way onto different surfaces and foodstuffs and start processes that surely predate us by a long stretch. We’re pottering around in an ancient miasma from which we can very easily benefit. I think that’s kind of amazing.

Fermentation, as a process, is the breaking down of molecules in an anaerobic environment (one without oxygen). It’s the changing of one thing into another, to alter the properties of the whole, via the action of enzymes. Fermentation is found across all cultures, applied to the grains, produce and tastes of every group of people. Where grain was abundant, we fermented it to make beer; where it was in scarce supply, we fermented cereal for kvass. Where grapes were so plentiful they rotted on the vine, we figured out wine. With milk, we made yogurt. With rice and daal, we made dosa. With soy beans we made tofu and miso. With herring we made surströmming. And with fruit, the possibilities are endless.

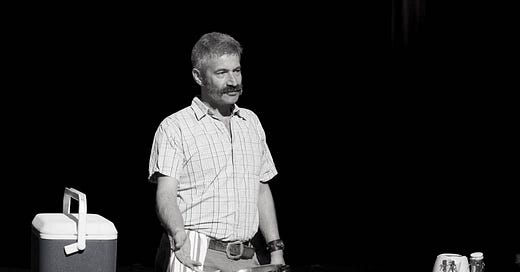

A lot of the things I know about fermentation I learned from Sandor Katz. The name might mean nothing to you, but he is well known amongst the type of people who buy dry soybeans and packets of koji to make tempeh at home. His 2012 book The Art of Fermentation was a New York Times bestseller and took fermentation from the realm of obsessive hobbyist into hipster restaurant kitchens all over the world. It’s the kind of book that changes the way you look at the world, turning you into a person who buys overripe fruit, hoards Kilner jars and refers to the cupboard above your fridge as the ‘fermentation chamber’.

As a person, Katz is equally as fascinating as the processes he writes about. He’s been publishing books on fermentation for twenty years, starting with Wild Fermentation in 2003, but was known as an ‘underground foodie hero’ well before that. A New York native born to an Ashkenazi Jewish family from Belarus (then the Soviet Union), he was working in municipal government and organising with ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) in his home city when he was diagnosed HIV positive in 1991, before there was any effective treatment for the virus. Realising that his job and activism was taking a toll on his health, leaving no time for him to look after this new self, he moved to a Radical Faerie community in Tennessee, where gay men (and now queer people of all stripes) live in rural communes that seek to be anti-establishment and radically accepting, focused equally on secular spirituality and environmentalism. Though Katz eventually left the commune to live nearby, it was here that he was introduced to fermentation—to how bacteria, viruses and fungus can transform living things—and begun to see it as one of the tools he could use to improve his health and live a better, more centred life. As he recounts in this Rowe Centre interview:

‘I was hoping that getting out of that schedule and being active and outdoors with good food and beautiful spring water, that kind of healthy living, was going to keep me healthy. That was my earnest hope. It wasn’t like I went into it thinking if I eat sauerkraut I’m going to cure HIV, but it seemed like a lifestyle in a rural area might help keep me healthy.’

Katz is at pains to remind people that he owes his health to the anti-retroviral drugs he has been on since 2000, like so many other people living with HIV. He never claims that a diet can achieve what medication can. But what he did find was that focusing on fermented foods supported his gut and digestion to stay healthy where other people on long term medication seemed to suffer. He was convinced—not only of fermentation’s ability to help him, but of the possibility that it might help both other people, and society generally.

It’s clear that for Katz, contracting HIV was the catalyst for a whole new type of existence; as he told the Rowe Centre, on receiving the news of his positive status, he said to himself: “I’m going to change my life.” This is eerily familiar to me, as a very good friend of mine—one who came to that brunch with me several weekends ago—went through an almost identical process when he, too, contracted HIV.

Josh was diagnosed positive in his 20s. Previously kind of rudderless and in that strange stage of adulthood where you are still unsure of what it means to be a grown up, as so many of us were in our mid 20s, he took his HIV diagnosis as an opportunity to change things. He immediately started taking medication and his virus levels became undetectable (meaning that he now cannot pass on HIV). Now, almost a decade later, he has taken chances that he might never have taken before; he is an HIV activist, has supported and mentored people with HIV across all age groups, and knows exactly what he will and won’t accept from life. He eats great food, drinks good coffee, walks his dog; he is the healthiest, the most himself, that he has ever been (and is a member of the friendship group we call Gout Club, for our tendency towards splurges on incredible meals and wine). For Josh, diagnosis was the start of his process of becoming self-actualised, so much so that his friends and family now celebrate his diagnosis date, October 31st, as his ‘HIVersary’, or second birthday. His mum gets him a card. It’s in my Google Calendar.

Twenty years have passed since Katz wrote his first book, and now we are all convinced of the possibility of fermentation to improve our lives; we understand that it is the microrganisms we encounter that hold the key to change. Of course, these microorganisms can do us harm; moulds can kill, and bacteria can make you violently sick, and even yeasts exist as ‘killer toxins’. But they can also benefit us, helping to change one thing from one state into another. Even in the most unexpected ways.

In the midst of the first wave of Covid lockdowns in October 2020, Katz released a strange and meandering book called Fermentation as Metaphor. I got a copy of this as a gift the Christmas of that year, the one that my partner and I spent alone in our flat, our families hundreds of miles away and our friends just across the road but not allowed into our house, to stop the spread of a virus that had taken over the entire planet. In the book, which I adore, Katz talks about microlife and degrowth; about the concepts of purity and contamination; about dissent and the political weaponisation of the concept of ‘pure blood’. He talks about the fantasy of a life that’s ‘uncontaminated’; about how we live with and amongst viruses and bacteria and yeasts and other microorganisms, and how we in fact rely on them. ‘We live in a contaminated world of constant microbial exposure,’ he says. ‘If purity means a state devoid of contamination, that is pure fantasy.’

The recipe that I ran home to make a few weeks ago was tepache, a lightly fermented Mexican drink that’s made from the peels of pineapples. Like many contemporary fermented foodstuffs, it started life somewhat different to the version we have now; the name tepache is actually a variation on its original Nahuatl name tepiātl, which means ‘a drink made from corn’. It was thought to have been fermented and enjoyed by Aztec labourers, and its process is shared by many drinks still popular across Central and South America—I’ve drunk chicha fuerte, a very strong alcoholic fermented maize drink, with workers off the clock in the Mamoní Valley rainforest in Panama, and suffered the next day. Tepache, though, doesn’t really produce alcohol, and if left to ferment for more than several days takes on the consistency of runny snot, and eventually will turn to vinegar. For our purposes, it’s finished within three days, contains probiotics and has a vitamin content higher than the pineapple its made from.

Making tepache at home couldn’t be easier. It more or less shares a process with kombucha, but where kombucha-making typically requires the introduction mother culture (so someone has to give you part of their established SCOBY, or ‘symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast, which looks like a kind of placenta), tepache will make its own from the natural yeasts that exist on the pineapple rind. The process is as simple as putting the rind, some sugar and a couple of cinnamon sticks in a jar with a load of water and leaving it for a few days. If you have a decently sized Kilner jar, you’re set.

What I like about tepache, as a kind of easy introduction to fermenting drinks, is that it’s as adaptable as it is simple. You can make it with what you have, which, in the UK, is probably white sugar and cinnamon sticks. You can go properly traditional, and use brown sugar, noticing the way that the flavour is deeper and more complex, or you can go rogue and replace the spices, add more fruits—whatever you like. As with all fermentation, temperature is a key factor in how long is needed for the final product to be ready. Tepache fermentation occurs most fruitfully (if you’ll excuse the pun) at about 26 degrees, and if you’re in the UK right now your ambient home temperature will be a lot lower than that. If you aren’t the kind of person who has a heat mat (and despite me being exactly that kind of person, I don’t have one), then you should note that the process will take a little bit longer in a British winter. But even with the frosty temperatures of a Scottish December, leave water and pineapple rinds and sugar in water, and tepache will be produced. All you have to have is patience.

I have been thinking so much lately about what it takes to change a structure; how it is possible to face something that seems insurmountable and remain hopeful. What I find incredible about fermentation is that what’s required for change is found naturally on the thing itself. With tepache, sourdough, wine, in fact almost every fermented product, what’s harnessed is the power of the natural yeasts that exist on its surface; the item itself carries what’s necessary for it to be completely transformed. Think of naturally fermented wine: in its ‘purest’ form it is the juice of grapes, with nothing added, left to ferment until it changes itself. When we drink it, we too enter an altered state—all because of the yeasts that naturally occur on the skin of those grapes. Restaurants and fermenters and wine producers and all sorts of food people have become obsessed with natural ferments because the process feels more congruent; why sanitise things only to add bacteria or yeasts in later on? You might as well let nature do its job. In the context of today, when so much energy, money and science is applied to sanitise our environment, the fact that even supermarket fruits and vegetables can make it to our hands with yeasts and bacterias on them feels like some sort of miracle. Even today, with everything against it, all you need to do is create the right conditions and the process will, inevitably, occur.

In Fermentation as Metaphor, Katz digs into the ‘profound metaphorical significance’ of fermentation. The word itself comes from the Latin fevere, to boil; we say that concepts ferment within us, whether they be, as Katz lists, ‘intellectual, social, cultural, political, musical, religious, spiritual, sexual’, driven by ‘hopes, dreams, and desires; or by necessity, desperation, and anger’. The drive towards fermentation is not sanitised; it is messy and contaminated, as we all are. It can be hard to spot it, at first; just a bubble here and there in an entity that seems otherwise unchanged. But before you know it, something is altered completely. As Katz himself writes:

The path of least resistance is to go with the flow. But in any situation, there are people who refuse to do so. The rebellious spirit manifests in different ways, but like fermentation, it is a force that cannot be extinguished.

If you’d like to support these essays, you can become a paid subscriber for just £6 per month. Alternatively, you can share this post on social media.

With thanks to Josh for his help with this post. If you’d like to read more about living with HIV in 2023, you can do so here.

Oh I’ve been meaning to buy his book for a while, and this is the final push. And what an amazing life story. Wow! I think this is particularly helpful now that people’s immune systems have taken a whack with Covid. Fermentation is the besssttt. Also Gout Club is the best thing I’ve ever heard.