In 2011, Penguin published a book called 100 Artists’ Manifestos: From the Futurists to the Stuckists. Across exactly a century, it traces the popularisation of the artists’ manifesto from The Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism, published in 1909, through the many variations and responses to that document, across Dadaism and Surrealism and all the way to the Stuckists in 2009. Artist manifestos aren’t so popular now, or at least they are just another piece of content in an endless whirlpool of content; now everyone has a three-line bio that nails their colours to the mast, and they make statements constantly, publicly, permanently. What need of a manifesto?

On the 20th of February 1909, however, a manifesto was big news; the Manifesto of Futurism was published on the front page of the French daily Le Figaro, and it announced the start of a new artistic movement. The editors of Le Figaro, though, knew how incendiary the manifesto would be, writing in the preface to the piece:

Is it necessary to say that we assign to the author himself full responsibility for his singularly audacious ideas and his frequently unwarranted extravagance in the face of things that are eminently respectable and, happily, everywhere respected? But we thought it interesting to reserve for our readers the first publication of this manifesto, whatever their judgement of it will be.

You would think such a caveat might be applied to a political manifesto, less so an artistic one—but in the time of modernism, such distinctions no longer held. The document being responded to / lampooned / rewritten by the Futurists, The Communist Manifesto, greatly understood the importance of rhetoric, of the art of speaking, so much so that Marxist humanist philosopher Marshall Berman called it the ‘first great modernist work of art’. Both poetry and the language of evangelism are woven into The Communist Manifesto:

All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.

In the often-quoted preface to one of his own works years earlier, Marx famously described religion of the ‘opium of the masses’—but he also wrote that ‘Man makes religion; religion does not make Man’, and ‘Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering.’ For Marx, religion was just as much a pronouncement of material conditions as poetry, as political rhetoric; why not bring the three together, if your goal is to appeal to the everyman, the worker, the God-fearing, poetry-reading masses?

Just as the Marx and Engels understood that political language has to be lyrical and rousing to appeal properly to the public, the poster boy of Futurism—Filippo Tommaso Marinetti—understood that the artist’s manifesto was ripe for the elevated bombast of the political. Where art seeks a reaction, no matter what the reaction is, what can be better than the crudely political? And the crudely political, the reactionary, the provocative is what the Manifesto of Futurism contained, seizing on the moment of change within Italy, the schism between the rapidly modernising north and the more traditional south, and cramming itself into the widening breach:

It is in Italy that we are issuing this manifesto of ruinous and incendiary violence, by which we today are founding Futurism, because we want to deliver Italy from its gangrene of professors, archaeologists, tourist guides and antiquaries. Italy has been too long the great second-hand market. We want to get rid of the innumerable museums which cover it with innumerable cemeteries.

Marinetti, from the first paragraph, positions himself and his peers as fevered artists near to bursting with a Futurist, nationalist pride; they are battling with logic, staying up all night to make their ‘frenetic writings', evoking all manner of loaded symbols: the lion, wild dogs, sharks, and the Centaur (a figure later used by Primo Levi to symbolise Fascist anti-Jewish hatred). After the maniacal introduction, he gives us ten points of manifesto towards the Futurist vision of an emerging Italy, grasping for danger, speed, violence and technology—which, in the middle, veers into seemingly far-right incoherence:

7. Beauty exists only in struggle. There is no masterpiece that has not an aggressive character. Poetry must be a violent assault on the forces of the unknown, to force them to bow before man.

8. We are on the extreme promontory of the centuries! What is the use of looking behind at the moment when we must open the mysterious shutters of the impossible? Time and Space died yesterday. We are already living in the absolute, since we have already created eternal, omnipresent speed.

9. We want to glorify war—the only cure for the world—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill, and contempt for woman.

10. We want to demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice.

The inclusion of these explicitly pro-violence, pro-war, misogynist positions is treated in discussions of the manifesto as if it is nothing more than artistic provocation. The preface to 100 Artists’ Manifestos introduces Marinetti as ‘philosopher, novelist, playwright, poet, propagandist and self-publicist, the Napoleon of the Futurist legions yet unborn, the Trotsky of the Futurist revolt yet unachieved.’ So far, so weirdly politically non-political. Nietzsche is mentioned briefly as an influence; so too Zola and Whitman. The evolution of the Manifesto of Futurism across its various versions, responses and other artists’ refutations is mentioned; any extension of Marinetti’s thought into the political realm—into action—is not.

To the art critic, Marinetti was a provocateur, a figurehead, the stick poking the bear of an emerging Italian identity. All his writings were partial jest, his words and rhetoric separate from the political. In Lesley Chamberlain’s 1989 introduction to the English edition of the La Cucina Futurista, the Futurists’ Cookbook—a continuation of the ‘joke’ of Futurist food, published in the second wave of the movement—the writer describes Marinetti thus:

No one who has seen Marinetti’s consistently arrogant pose in photographs—is if he were defending himself against the new medium—will think of him as a gentle man. Yet we have the testament of his family that he was a devoted husband and a father to his four children and of those close to him that he was a generous friend.

The easy—and, I think, correct—reading of the Manifesto of Futurism is as a deliberately provocative artwork, rejecting the liberal attitudes of the time, responding to and representing the cultural discussion surround technology; of the future vs the past. The north of Italy was rapidly industrialising, the south remaining more rural, more wedded to tradition; the centralist state, the bringing together of two parts of Italy, was a hotly debated topic. The Futurists embraced modernity and resisted what they described as authoritarianism, and bureaucracy, and for a time it seemed it might have readily formed alliances with the left as with the right, as it centred (or claimed to centre) the proletariat first and foremost. Ultimately, though, Futurism’s insistence on nationalism and a glorification of war pushed it further and further away from the left.

Art has often strayed to the right, or adopted the positioning of a person on the right; many novels are written from the perspective of racists or colonialists or misogynists for artistic effect, something that can become more complex when it is a technique employed by performance artists—David Bowie’s Thin White Duke era being an obvious, troubling, cocaine-driven example. It is actually unhelpful to respond to these artworks by claiming an intent that is outside of the project; despite the endless debate, Lolita is not a pro-child-abuse book. If the Manifesto of Futurism was the end of Marinetti’s forays into the right-wing space, it would be ridiculous to call him a fascist. But it was not.

In the years following 1909, Futurism slowly moved away from being an often anarchic artistic space to become a more explicitly political movement. From public readings of their manifestos, in which the audience was encouraged to throw vegetables at the orators, some of its exponents turned towards real, violent action and engagement with the political right. After the Italo-Turkish war, Marinetti became more strongly focused on the emergence of Italy as a modern, powerful nation; he was tipped to stand for the 1913 general election, but did not. By 1915 he was being arrested alongside Mussolini; in 1916 he supported Italy’s war effort with pro-war rhetoric and by 1917 he was in active service. In 1918, Marinetti founded the Futurist Political Party; just a year later, it was collapsed into Mussolini’s Fasci Italiani di Combattimento (Italian Fighting Leagues), with Marinetti sitting on its central committee. In 1919, Marinetti was one of the arditi (ex-servicemen against socialism) who destroyed the office and printing works of the socialist newspaper Avanti!, an action which showed Mussolini how effective armed intimidation and violence could be against political rivals. In 1921, the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento was reorganised into the National Fascist Party; Marinetti and many of the Futurists, then, were some of the first official Fascists.

You would think that being a card-carrying, active Fascist who, even outside the official engagement with the party, espoused and supported the same aims as Fascists throughout his life, would put to bed any question of whether or not he was one. But this is not the case.

Marinetti and others briefly resigned from Mussolini’s party in 1920, calling the group ‘reactionary’, but by 1922 they were back. According to the introduction to La Cucina Futurista, ‘he never became so deeply engaged again’. But in 1926, Mussolini personally selected him as a founding member of the nationalistic Italian Academy, and by 1932, The Futurist Cookbook was published, echoing explicitly Fascist ideals, including the refusal of ‘foreign’ words like ‘menu’ and ‘sandwich’ and a call for the abolition of pastasciutta (dried pasta), saying that it made Italians un-virile and lazy. Marinetti sought to have Futurism made the official state art of Fascist Italy but failed, because Mussolini had no real interest in art; when the antisemitic Racial Laws turned public opinion against modern art in the late 1930s, Marinetti responded by stating that there were ‘no Jews in Futurism’. For the rest of his life, he by turns opposed Fascism’s approach to the art world and the concept of internationalism, and attempted to regain his position within Fascism. And yet, according to the introduction to La Cucina Futurista:

His Fascism remains a hotly-debated question, again one not helped by Marinetti’s constant interweaving of art and life.

People change, and switch sides; a racist can become an anti-racist, a socialist can become a fascist, a Tory can convert to the Green Party. These things are all possible. One thing you do should not define your whole life. It is foolhardy, though, to insist that a person is or isn’t something based solely on what they say, if this is in direct opposition to what they consistently advocate for and do.

Last week, in response to a spate of highly-organised, far right racist attacks on communities housing immigrants and asylum seekers, leading to further direct racist attacks on Muslims and Black and brown people, a years-old clip of rapper and writer Akala speaking to Tommy Robinson on Question Time was re-shared on social media. In it, Akala (who wrote the must-read book Natives), explains the structure of racism in the UK, and the way it is bolstered and further by the media; he explains Tommy Robinson as a functionary of this, in the face of a spluttering Robinson who constantly attempts to talk over him, to say things like, ‘He hasn’t explained what I’ve said that’s racist,’ and ‘I had four Muslims at my wedding.’

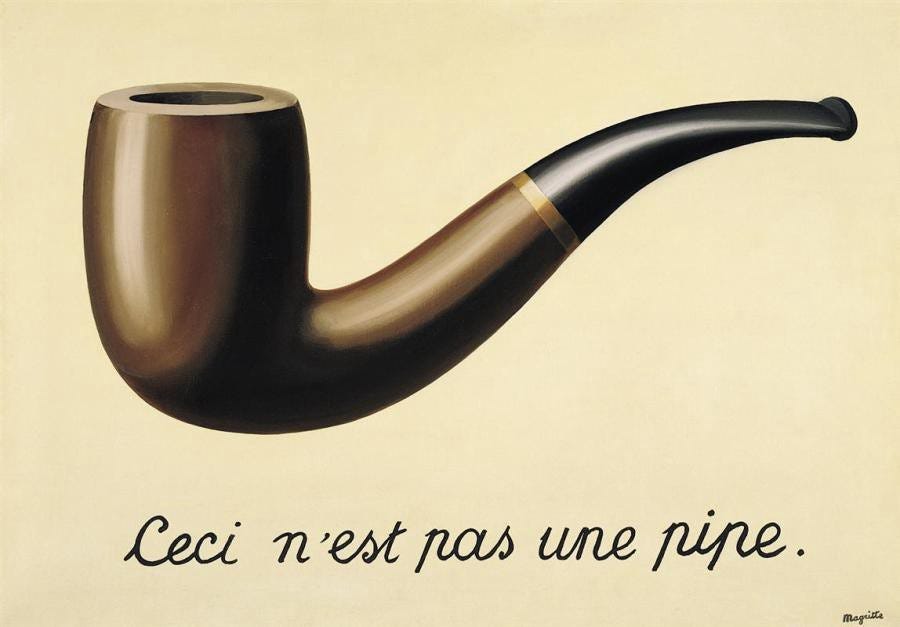

It calls to mind the phrase, used by crowds on Twitter defending people who sit on the internet all day sharing photos of trans women and calling them men, demanding investigations into women who do not look feminine enough, pressuring politicians to rescind the possibility of gender-affirming healthcare and encouraging people to police the existence of whoever does not fit into their narrative of what a woman looks like: what has she said that’s transphobic, though? Or, an earlier version of this, about the world’s most divorced men, who constantly use the most despicable terms for Black and brown people, get in bed with the far right, and do things like burning pride flags: how is he homophobic/racist? These are bad faith questions, only intended to distract. To these people, there is simply nothing that would meet the threshold of being labelled transphobic, or homophobic, or racist; you can wear blackface, you can compare racialised people to animals, you can deny the archival proof of trans people being targeted by the Nazis, and still they ask: what exactly have they said to prove that they are? You can be a member of the National Fascist Party, and believe in Fascist ideals, and still have the historical record refuse to admit that you were, at least at one point, a Fascist. They are pointing at a pipe-shaped smoking device being used as such by a smoker, a pipe-shaped device which has also co-written the Pipe Manifesto, been a card-carrying founder-member of the Pipe Party and tried to make its own artistic movement the official art style of the Pipe state, and telling you it simply is not a pipe.

In the UK right now there are plenty of people who insist they’re left wing despite holding some of the most reactionary views you could hope to imagine; there are people who insist they’re left wing despite viciously attacking any successful leftist project (to the benefit of the right) and criticising any other leftist who does not fall perfectly in step with them. There are people on the extreme right who insist that they are fighting fascism by attacking diversity measures and any attempts at racial or social justice. When we speak about politicians we parrot what their PR teams have pushed out into the media rather than the things they have voted for or against, and what their work for their constituents has looked like; often these things are diametrically opposed, and always we fall for the narrative. Sometimes, the narrative about them comes from the press, to demonise progressive candidates, and we fall for this almost 100% of the time as well. And the worst thing is that we never, ever learn.

Increasingly political positioning is something tethered more to what we declare, and what we share, than what we actually do. It’s easy to think that this is the fault of social media—the result of a mass moment in which people declare themselves ‘allies’ or ‘anti-racist’ or ‘pro-freedom’ or ‘left wing’ or any manner of things without actually doing any of the work to make this the case—but it has been around at least one hundred years, since the advent of modern marketing and its effects on the art world, since Marinetti successfully sold himself as just an artist or just a provocateur while becoming an active and effective member of the Fascist movement, and then passionately holding Fascist ideals from outside the party, from the late 1910s to his death in 1944. Politics, and our political understanding, has to be grounded in the material—otherwise, it is just a narrative.

To paraphrase a quote often misattributed to Freud: sometimes a pipe is actually just a pipe.

Thanks for this. Apart from explaining beautifully the depressing facts of so much we’re living with, you’ve reopened another perspective for me on Magritte and the themes in his work -although now perhaps he was culpable of the opposite and convinced his that art was merely art. Perhaps the ability to hide beneath this banner can save creative and challenging ideas in times of fascism. Let’s hope we don’t need to test this further!!

this is a brilliant piece.