will we ever stop being deranged about Lolita?

on misunderstanding literature to avoid discomfort

Recently, I read a book about monsters; about what we do with great art by people who have since revealed themselves to be monstrous, through having perpetrated the abuse of children, or rape, or racism, or homophobia, or antisemitism, or domestic violence, or any of the other myriad crimes we, as often awful human people, might commit. I am interested in the topic, and enjoyed the first few chapters, though found it eventually repetitive and increasingly shallow; for a book that purported to be about the audience, about not the art or even the artists themselves but about what we, as the consumers of their work, are supposed to do with the knowledge of monstrosity, it seemed to spend very little time really interrogating that.

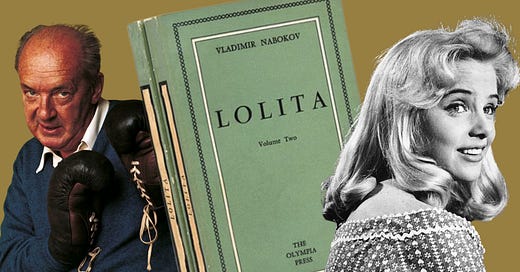

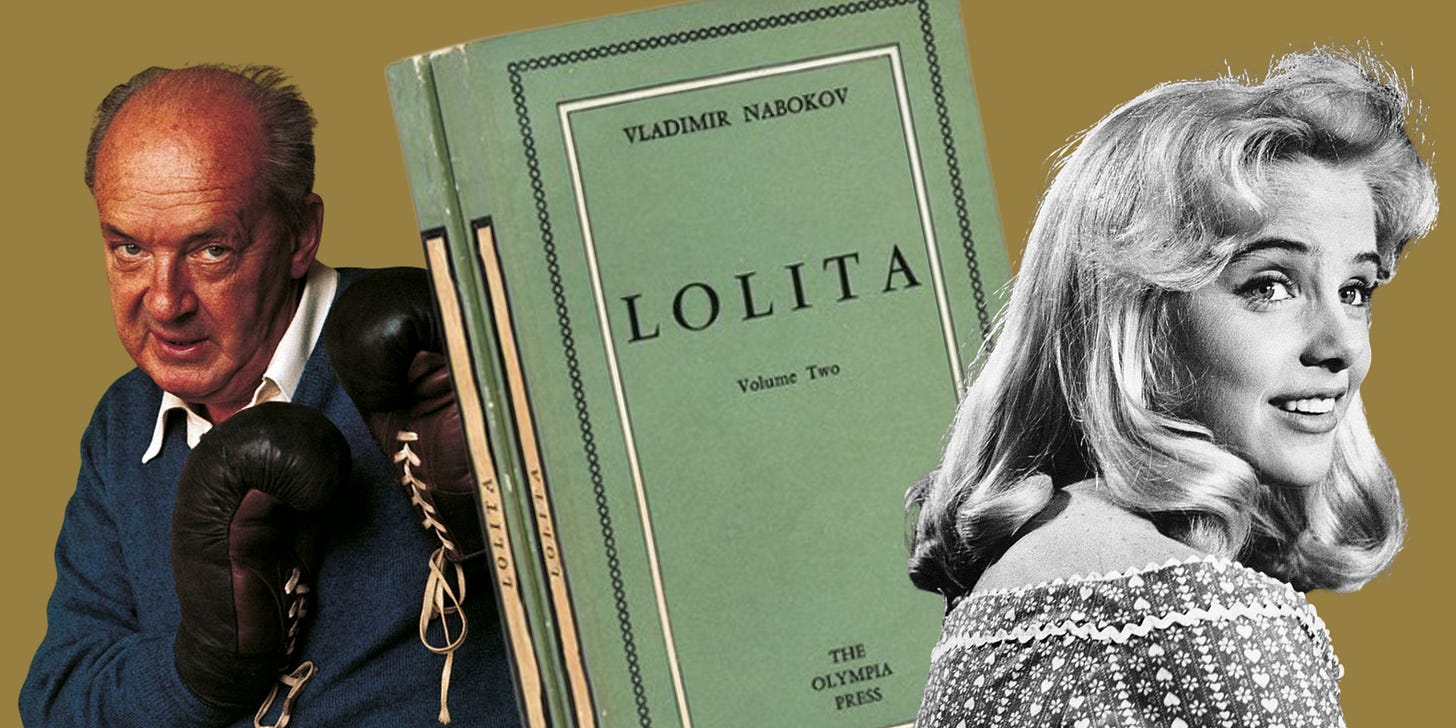

The first chapters of the book explicitly concerned the filmmakers Woody Allen and Roman Polanski, two men who have created masterpieces of cinema (Rosemary’s Baby is one of my favourite all-time films) but who have also been accused—and in the later case charged, though he fled the country before sentencing could be passed down—of the sexual abuse of children. Another chapter deals with the singer Michael Jackson, who has been accused, repeatedly, of the same. The seventh chapter of the book is about Vladimir Nabokov. What he did was write the book Lolita—which the author describes, in the first paragraph, as ‘a text that is perceived, in and of itself, as an act of abuse.’

It’s difficult, as a writer and a reader, to approach such a sentence with anything other than frustration, maybe even disdain. To approach it in a book that is mostly about rapists and child abusers, and which finds many reasons to defend the art made by those people, is even more challenging. Who, exactly, sees the novel Lolita as an ‘act of abuse’? Surely not anyone with a smidgen of critical thinking ability. The very fact of the chapter’s inclusion implies a moral equivalence between writing about child sexual assault and actually committing it—and yet the chapter on Nabokov is called ‘The Anti-Monster’; it includes the author’s critique of her own, teenage first response to the book; and the overarching feeling is that she is trying desperately not to imply too strongly that he was, in fact a paedophile, while at the same time structuring an entire chapter around asking if he was. There are many possible criticisms of Nabokov the man, but these are not the ones being made. So what is the point, in a book about real monsters, of indulging in this tired, anti-intellectual argument, one that has been hashed and rehashed approximately a hundred thousand times since this book came out in 1955, and which is offensive to both readers and writers alike? Why, for the love of god, are we having this conversation again?

Lolita, of course, is not the only novel which is written from the perspective of a monstrous character. It is not even the only novel to be written from the perspective of an abuser of children.

Hanya Yanagihara’s criminally under-appreciated first novel, the gorgeous and difficult The People in the Trees, takes the form of the edited memoirs of Norton Perina, a scientific researcher, formerly of Stanford, famous for his discovery of a species of turtle which imparts a form of near-immortality on those who eat its flesh. Except that he did not ‘discover’, this; rather, he took the knowledge from the indigenous people of the fictional Micronesian island of Ivu'ivu, and sold the knowledge to pharmaceutical companies, leading to the complete destruction and colonisation not only of the physical island but of the way of life of the people who lived on it. It is a novel that refuses to shy away from the brutal reality of the world we live in—in more ways than one.

I came upon The People in the Trees completely innocent to its context or contents—perhaps the perfect way to approach such a novel. I found it by accident in a bookshop in Bangalore in October 2015; though the soon-to-be-mega-bestseller A Little Life had just been published in the UK, I had not heard of it, nor its author. The novel was face-out on a shelf while I was looking for something to occupy me on the long flight home, and the cover—pale teal with a line drawing of half a turtle, orange-brown leaves adorning its back—caught my eye. The 29-year-old me was immediately swept away by Yanagihara’s vibrant descriptions of Ivu'ivu, and her obvious critique of the supposedly morally-neutral anthropological missions to micro communities and the capitalist exploitation of their resources. The book’s treatment of the concept of dementia—of the incredibly old ‘people in the trees’—spoke to me deeply, as my grandmother had died at the very end of dementia only a couple of years before. And then, of course, there was the child abuse.

Like Lolita, The People in the Trees puts the facts of the matter front and centre. The opening lines of the book are in the form of a news report, and say this:

Bethesda, Md.—Dr Abraham Norton Perina, the renowned immunologist and director emeritus of the Centre for Immunology and Virology at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, was arrested yesterday on charges of sexual abuse.

Dr. Perina, 71, was charged with three counts of rape, three counts of statutory rape, two counts of sexual assault, and two counts of endangering a minor. The charges originated with one of Dr. Perina’s adopted sons.

What follows is a foreword from Perina’s colleague Dr. Ronald Kubodera, which presents the memoirs of Perina himself; like Lolita, we learn almost immediately, this novel will present this terrible story from the perspective of its central monster, and it will show all of his attitudes, excuses, and details of the abuse he perpetrated. Like Lolita, it is a book that puts you, the reader, directly into the mind of a monster. And it does so incredibly well.

I have never once seen anyone speculate on whether or not Yanagihara might share the same proclivities as her protagonist; instead, I have seen the novel praised as inventive and unsettling, her characterisation praised as incisive and stunning. Presumably, this is because she is a woman, not a man, writing about a criminal man. Perhaps it is because her protagonist is based, semi-closely, on a real person: the Nobel Prize-winning Daniel Carleton Gajdusek, best known for his work on the transmissibility of the cannibalism disease kuru, a serial child abuser who was convicted of child molestation and who, like Polanski, eventually fled to Europe. But surely Humbert Humbert, too, is based on real people—not one specific one, perhaps, but an amalgamation of many versions of a type. And it’s often said that the character of Lolita was based on Sally Horner, an 11-year-old girl who was abducted by the serial rapist Frank La Salle, who posed as the girls’ father as he trafficked her around the United States—though Nabokov denied this influence, there are many parallels between the real case and Lolita.

If we can understand that the portrayal of an unapologetic rapist in The People in the Trees is intended as an inducement to a critique of the systems that give power to such a man, why can’t we accept the same of Lolita, which does exactly the same thing?

The author of the monster book asks this question while discussing Lolita, distilling her discomfort with the novel into something more personal: ‘why did Nabokov… spend so much time and energy on this asshole?’ The question implies that assholes are not worth writing about, that power—and who has it, and what they do with it—is not worthy of literary interrogation. The irony is that the author has written an entire book spending time and energy on assholes, asking the same questions about them as Yanagihara, but just in a more direct way. As Yanagihara put it, in an interview with Vogue in 2013:

It’s so easy to affix a one-word description to someone, and it’s so easy for that description to change: if we call someone a genius, and then they become a monster, are they still a genius? How do we assess someone’s greatness: is it what they contribute to society, and is that contribution negated if they also inflict horrible pain on another? Or—as I have often wondered—is it not so binary?

The question of monstrousness and what we do with monstrous people can be addressed in many ways. It can be discussed in a nonfiction book. It can be examined in interviews, or on panels at festivals, or with friends around a dinner table. And, as Yanagihara shows above, it can be explored in a novel, which is a form that we all purport to understand—until, it is, that it transgresses a particular, moving line, one that sits in different positions according to different people. As soon as a novel speaks too directly about something distressing or horrible, as soon as it dares to make the reader complicit by putting them in the perspective of a monster—then, we pretend that we don’t understand the project of a novel, nor the difference between a character and the person that writes him. We are placed in a state of collusion, and we are uncomfortable, and as an emotional response, we reject the novel outright.

Monsters, of course, are all around us. Monstrosity, all forms of it, is something that we all, as human beings with free will, are technically capable of. Monsters walk among us every day; we might marry them, or give birth to them, or work alongside them, or be them. Is a kind of performative suspicion of anyone who dares write these characters an attempt to deny the reality of this, to draw a line between us, as moral beings, and something that we know to be a lot more common that any of us would like to believe?

I have skin in the game here, because I too wrote a novel from the perspective of a terrible man, based on a real-life terrible man. This book was massively influenced by both Lolita and The People in the Trees, as well as Frankenstein, as well as American Psycho, about which I wrote my undergrad dissertation. In interviews about this book, specifically about writing a character who is racist, who abuses a woman in his life, who does the most reprehensible things you could hope to imagine, I am always asked if it was some sort of psychological assault to have to step into that mindset. And though the question is always well intentioned, I always want to say—why do you have to believe that? I know what such people think, and so do you. We live in a racist, misogynist world, run by racist, misogynist systems. Women’s bodies are assaulted, manipulated and mutilated all the time; every day of our lives black and brown people are oppressed by white supremacy. Bigotry, abuse, dehumanisation, murder—these things are all around us, normalised, excused, supported by systems of power. It is not difficult to channel that knowledge into fiction, or give those thoughts to a fictional character that you have created. Perhaps it is nicer to believe that we simply don’t understand these people. We do. They tell us what they think and feel all the time. We are all part of the system that produces them. They, in the grand scheme of things, are we.

And yet: just how did Nabokov come to understand Humbert so perfectly?

This is the question at the heart of this endless debate, put starkly by the author of the book on monsters. It’s not that he wrote about a child abuser, the claim goes, nor that he held up a mirror to the dark parts of society and made us look at them—it’s just that he did it so well. The book becomes suspicious exactly because it succeeds in its own project. Who could write an abuser so insightfully, without being an abuser himself?

The simple answer to this is that a good writer can, because it’s his job to do so. A writer’s pursuit is to interrogate and illuminate the human condition, in all its facets, both positive and negative. Part of the human experience is the awful fact that some adults abuse children, and have been both excused and forgiven for this for as long as we have had society. Books like Lolita engage with that terrible fact, and do so in a way that profoundly affect us. We can’t know whether Nabokov understood the mind of a paedophile perfectly, because we don’t have access to the minds of such people (assuming, reader, that you, like me, are not one). What Nabokov did understand is what people would believe of such a character. He understood that his readers, like all people, form an image of what such people must be like—that we do, on some level, know them. And this knowledge truly horrifies us.

The facts of paedophilia are not unfamiliar to us, as civilians. It is not a crime that is so rare it is unfathomable, and in the modern world neither is it so taboo that it is unspoken of, in the popular media or by those who have been victims of it. The public silence imposed upon abuse victims has been steadily dismantled over the last few decades. Many people have experience of being touched inappropriately by adults when they were children, whether that was a single instance or the start of something even more traumatic and ongoing. The NSPCC suggests that around 1 in 20 children in the UK have been sexually abused; these children grow up into adults, who spend their lives trying to process and recover from this abuse. We know them; some of us are them. And they know their abusers; it’s estimated that around 30% are abused by family members and up to 60% by someone known and trusted by their family. Victims of this abuse may struggle to speak about it to their friends and loved ones, but many do not; they open up about what they’ve gone through, the horrors of it, the lasting effects. I recently read the very brilliant book about witnessing the Ghislaine Maxwell case by Lucia Osborne-Crowley, The Lasting Harm, in which she writes powerfully on the effects of grooming and sexual abuse on the girls who were predated upon. One of the painful things about growing up is realising just how common this kind of abuse is, and how many people you know have suffered such things. Indeed, one of those people may well have been Nabokov himself.

In his memoir Speak, Memory, he recounts instances when he was around eight years old, when his uncle Ruka would,

invariably take me upon his knee after lunch and (while two young footmen were clearing the table in the empty dining room) fondle me, with crooning sounds and fancy endearments…

This passage has been endlessly discussed by readers of Nabokov. Some take it as evidence of familial abuse; others as a throwaway disparagement of a gay uncle. If it is true that Nabokov was touched by his uncle, does this bring a different bearing on Lolita? Perhaps, for some, it does—but I think that it should not. The fact is outside of the question of whether the book succeeds in highlighting a difficult and uncomfortable fact about the world: that is inarguable. It does. Demanding that our writers have direct experience of the horrible things they write about can only, in the long run, force writers to ‘out’ themselves in any number of ways, eroding the concept of privacy and feeding the bleak impulse of the publishing industry to exploit a person’s lived experience (which often ends up re-traumatising them, forcing them into a public position from which they cannot be removed) and narrowing the conception of what a novel is or can be. This has already happened, when the author of My Dark Vanessa, Kate Elizabeth Russell, was forced to state publicly that her novel, about a teacher grooming a teenage student, was based on her own experiences; though this was due to accusations of plagiarism, not criticisms of the work’s themes, Russell noted in her statement that ‘I do not believe that we should compel victims to share the details of their personal trauma with the public’. A novel is not a secret admission of a writer’s beliefs, nor their life story, nor is it a moral roadmap. It is a piece of entertainment that reflects the world, in both its shadows and its light. We can choose to read it, or not read it; we can dislike it, and critique it, and think the goal of the book a bad one. But a book that reflects darkness is not, itself, abuse. As Nabokov himself puts it, in the afterword to Lolita:

That my novel does contain carious allusions to the physiological urges of a pervert is quite true. But after all, we are not children…

The term ‘provocative’ is used these days to refer more to trolling than anything else, but to ‘provoke’ someone, as this kind of literature does, means to stunt them out of a comfortable position, to force them to have a response to something. This is what books like Lolita do; they show you something cruel, and bleak, and terrible, and they ask you to consider how you stand in relation to it: if you condemn it, if you support it, if your place in the world allows it to happen. This literature is provocative because we would prefer not to think about these things. We would prefer not to acknowledge the commonplace nature of abuse, whether that is of children, or of women, or any other vulnerable population—instead, pretending that the threats women and girls face is from strangers in public toilets, or weirdos in cars, or serial killers, all of which are startlingly statistically unlikely. We prefer not to think about the fact that our daughters, if we have them, are vastly more likely to be assaulted by our husbands, or their fathers, or our fathers, or a family friend, or their gym teacher, or the kind-seeming neighbour next door. These truths are painful. But they are true.

Does our ability to critically engage with art that shows bad things decrease as the world around us shows us those same things? Does the constant awfulness of the world erode our ability to be emotionally resilient to fiction? I know that as I get older, I find things more emotionally stressful; I find it harder to read the most graphic parts of American Psycho, to watch films in which someone loses their loved one, to see racist violence deployed on screen. A few weeks ago I saw a film that was tonally weird, poorly directed and overlong, and still I cried intensely as the mother character watched her terminally ill daughter die. Over the summer I went to see Dune 2 and felt viscerally sick in the middle, so powerfully did the film (completely unintentionally) mirror what was (and is) going on in Gaza. But the key point here is that none of that, none of my response, casts a moral case on the art. Just because I personally find something too upsetting to read does not mean the author was wrong to write it. The intention of art is to provoke a response. It doesn’t make it morally negative if it does.

Of course, you can write abhorrent books. You can write books that are cruel about people, or lie about history, or push false agendas, or pull the wool over the reader’s eyes. You can use offensive language not to show how disgusting such things as racism and transphobia are, but merely to be racist, or transphobic, or classist, or ableist. Discerning intent is the key, and it requires you to read generously, curiously; you have to read with your mind open to the idea that perhaps the writer’s intention is not what it immediately appears to be. It is an act of faith in the reader to bury the meaning of a book in the subtext, or even deeper; the writer believes in your ability to think for yourself, to work out meaning from the clues they have left. If a book is difficult, the writer has decided not to patronise you, not to beat you over the head with the fact of their intent. They have written with the assumption of a generous, thoughtful reader. You don’t have to be this reader—but you’re going to be missing something if you don’t.

Next September, Lolita will be 70 years old. It is not difficult to find information about its author, his experiences, or the endless ways that readers have engaged with this book. There are a thousand more interesting questions, more illuminating questions, to ask ourselves as readers than ‘does writing about something monstrous make a writer a monster’—such as the ones asked, and answered, by the brilliant Lolita Podcast by Jamie Loftus. But you do not actually have to go into the work of others to understand what Nabokov by writing Lolita; all you have to do is read the fictional preface to Lolita itself, written by the fictional John Ray Jnr. Ph.D., a character invented by Nabokov. The meaning is wrapped in irony, in diversion and distraction, because that’s what Nabokov did, of course. But in there, if you look hard, there is a nugget of truth:

‘Lolita’ will become, no doubt, a classic in psychiatric circles… for in this poignant personal study there lurks a general lesson; the wayward child, the egotistic mother, the panting maniac—these are not only vivid characters in a unique story: they warn us of dangerous trends; they point out potent evils. “Lolita” should make all of us parents, social workers, educators—apply ourselves with still greater vigilance and vision to the task of bringing up a better generation in a safer world.

Loved this essay, so brilliantly written and argued. I agree that the question “how could Nabokov write such a monster if he was not himself a monster” is absolutely baffling and out of place with all those other ACTUAL monsters the book mentions. To ask this question is to not know Nabokov’s style - his books are seeped in irony, forcing the reader question the functional reality and the trustworthiness of the narrator. To take it literally is, well, missing the point.

As I kept reading, American Psycho came to mind and how no one thinks Bret Easton Ellis is capable of doing any such things. I’ve seen the book you refer to around and read some bits here and there as I was interested in the question of good art by bad people, or more precisely whether we can separate the art from the artist. But the example here of Lolita is of course a different one and I have enjoyed reading your thoughts on how fiction should be taken as such without assuming is necessarily a reflection of the writer’s lived experience or true nature.