Building the Fork is an occasional series on upsettingly good meals that I have eaten. This is not a restaurant review; it is the work of someone who will cry over a dish of food given the right circumstances.

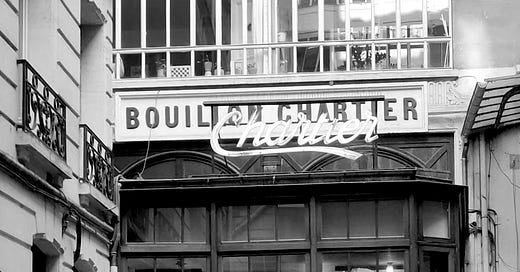

It is the height of summer in Paris, and I am hungry. I am only here for a few days and can’t stand the idea of sifting through TripAdvisor trying to find a good but moderately priced non-touristy restaurant, so I go for cheap and interesting instead. I end up at something of a Paris legend: Bouillon Chartier.

It’s early evening and I make my way to the original location, in the Grands Boulevards district; in contrast to the austere place settings, the actual space, a high ceilinged Belle Époque dining room, is stunning. Due to its wild popularity, the Bouillon Chartier operates a single-rider system much like theme parks: if you’re riding (or in this case dining) alone, you will be fast-tracked to wherever there is space. These guys are working to economies of scale that require every seat to be filled. The first time I go, I am seated at a four-person table next to a Spanish couple. I smile and say bonjour, and open up my book to read. I love shit like this; I thrive on potential awkwardness, in situations where the whole thing could go south on so much as a misplaced look, where there is a required level of civility that does not come naturally to many in modern society (including, often, me). I suppose it is a test of humanity; look, we’re here now, and you’re going to have to make the best of it. Can you?

Bouillon Chartier feels like a relic of the time of Sartre and de Beauvoir and Camus; a place where your poor intellectuals and your future starlets might eat for relative pennies, spilling wine on dog-eared copies of the latest white-covered publications and arguing about politics. It is busy and forgoes all the niceties of the contemporary restaurant experience; it is intended to feed you, not coddle you. Quickly a young Chinese student is sat opposite me. We’re facing each other and the table is small; in such enforced intimacy it would be more effort to pretend that the other person doesn’t exist than to engage in polite conversation. I say hello; he responds. We chat. He is from Shenzhen and is surprised that I’ve (very briefly) been; he has read The Second Sex and found it very academic (which it is); he flatters my French, which can only mean he doesn’t speak any at all, given that my French is atrociously pronounced and learned entirely from Duolingo. We settle into a slightly unwieldy silence while we eat and it makes me smile. He eats quickly, while I am here for the full experience, ordering a starter, main and dessert with wine and a post-dinner espresso (the main is a baked sea bream, the dessert a divine chocolate mousse; the wine is a sparkling white for 4 Euros). I am sporadically beaming at the chaos of the service around me. The staff size up their diners and speak in whatever dialect they think the guest will speak; they write your orders on the paper tablecloth in pencil, to be totted up at the end of the meal. Proximity requires both me and my co-diner to smile at and pass things to the Spanish couple; I feel incredibly smug by saying something in Spanish and enjoying the fact that now a handful of people think I know Languages, whereas in fact I am fucking terrible at them. When the Chinese student gets up to leave we say one of those gentle goodbyes you produce when you know you will never see this person again in your whole life. My entire bill, scribbled on the table, comes to 27 Euros. When I leave, I am practically walking on air.

I enjoy the experience so much that I return the next day, slightly earlier; I’m booked to watch a (very bad) Wes Anderson movie at an art deco cinema so when I am seated, the place is only a quarter full. Immediately the vibes are a little off; there is an Australian couple at the table next to mine and they are distinctly not enjoying what they’re eating. The food here is simple; French classics done cheaply, but with an obvious focus on the quality of the meat and fish. You might get bourguignon with cheap plain pasta, a blood sausage with a dollop of mashed potato, a pork chop with tinned potatoes. There is always a three course set menu for 15 Euros, which is less money than one dish will cost in every other restaurant in Paris. There is a ‘wine of the moment’ for 7 euros a half-bottle. I don’t know why you would come here with expectations of grand dining, but this couple are actually mocking the food, acting like recalcitrant school children. I find myself watching them, finding their behaviour rude and obnoxious. The wine tastes a little sour.

The pre-theatre crowds begin to arrive; I am alone at a four-person table, knowing it will be filled up. As I am eating my starter and reading Annie Ernaux, I hear an American woman feet away; oh my god, no. I can’t sit with her! Absolutely not. She circles my table as if terrified of being caught in its gravitational pull. The staff are trying to explain that this is how things work, and she momentarily forgets that other people in one of the world’s most popular tourist destinations might also speak English: what would SHE think of it? No, I need my own table.

She gets her way, and I turn to look; she looks physically affronted by the idea she might have had to sit opposite me. I consider calling over to her, and saying you know, I don’t have the plague. Sometimes it’s fine to have to share space with people. But I don’t, and instead look back sporadically throughout my meal, noting her discomfort when she is inevitably invaded by other diners. I start to listen to accents; generally the American tourists are having a hard time here, uncomfortable next to strangers, at the lack of forced-smile service, at the reluctance to cater to their desires; I can’t imagine a menu adjustment would go down well. Some of the Brits and Australians, too, don’t think much of this place. I don’t linger as long as I did the night before, but I do order the chocolate-drenched Chartier profiterole, the first I have eaten in about a decade, given to a) a ten year veganism and b) an absolute lack of self control around choux pastry. It is nothing short of heavenly. I know I won’t come back.

In writing this, I come across a May 2023 New York Times article on the ‘radical act of eating with strangers’, which waxes lyrical about a new supper club project that brings together eight people to dine together. I find myself kind of taken aback that this is considered avant-garde; surely people eat with strangers all the time? What about when you’re at a packed cafe, taking up only one space of a two person table, and someone else wants to have a coffee? There are some people whose neurodivergence and other sensitivities would make this kind of socialising difficult, but this seems to be beyond that; a cultural difference in whether or not we find it normal to share a table.

It strikes me that maybe I have eaten with strangers an above average amount of times in my life. At residencies, where you’ll eat with relative strangers for a month at a time; while travelling, at farm tables or with hosts or, indeed, on a plane; at networking dinners or stand up lunches, politely trying to get hold of the last vol-au-vent without looking greedy or uninterested in someone’s chat. The only time I have found this a trial is at a Buddhist retreat outside Sydney, on a three-day long silent medication course where you were not allowed to sit with your friends and had to chew every mouthful of your pallid vegan meal thirty times before swallowing. I hated this experience deep down in my bones, and still bristle at the memory. Chewing thirty times isn’t mindful; it just makes every mouthful of food tasteless and disgusting. Sitting in an abject, strained silence and not making eye contact with strangers isn’t communal, it’s tortuous. It felt, for me, inhumane.

Why do I still consider this experience to be so awful? Perhaps it is the same reason that the American woman practically fainted at the idea sitting opposite me to eat. Eating makes you vulnerable; you have to recognise each other’s base physicality. When animals eat, they are most open to attack, distracted and soft. In her book The Rituals of Dinner, Margaret Visser says that table manners are ‘a system of civilised taboos which come into operation in a situation fraught with potential danger. They are designed to reduce tension and protect people from one another.’ She goes on:

we may be slicing and chewing; we may have killed or sacrificed to supply or feast; we may be attending to the most ‘animal’ of our needs; but we do so with control, order, and regularity, and with a clear understanding of who is who and what is what… At table we are both armed and vulnerable; we are at such very close quarters.

Put two people across a table from one another and it is even more exposing; you might catch someone’s eye while piling wet noodles into your mouth, open in all regards. Not only are you physically assailable, you’re socially vulnerable too. It’s hard to eat demurely, and boring to do so; for me, having to attend to any notion of table manners really takes the pleasure away from eating. I want to lift a bowl to my lips and slurp the end of a soup, I want to run my index finger round the last splatterings of sauce, I want to spill all the way across the table as I make a friend taste what I have ordered. I think often of my friend Catriona, a former personal chef, who micromanages the first forkful when she’s cooked for you: get a bit of this, a bit of that, and then a crunchy thing. That’s how I want to eat, whether the person across from me is a stranger or a loved one.

Perhaps it comes down to how we see the world—or, more precisely, the experiences we’ve had in it. For me, the person slurping pasta across the table is someone I might have a brief but intimate relationship with, one that’s free from the social pressures of longer-term association. I don’t have to pretend to have manners or be cultured because it matters so little what this person thinks of me; either we will spend our short time together in a pleasurably awkward dance or we will hate each other. Either way, its going to be over forever in a matter of minutes. For the American woman, the weight of a stranger might be heavier, her vulnerability more acute. I think of my cats, raised amongst other hungry strays, taking food from their bowls to somewhere less seen, less open to attack. Perhaps the openness to sharing a table comes from privilege, and should be seen as such. There are such things as plagues after all.

Realise that I went here on a school trip to Paris. Our teacher waxed lyrical about the place. We probably moaned bc it wasn't like Pizza Express. Appreciate the experience and the memory now

Your words have really made me reflect on my own relationship to communal eating...Whenever we go to The National Theatre, we eat at the streetfood market regardless of the season, due to the communal eating element. We end up on a table with a bunch of strangers, all with different cuisines, diffferent ages, backgrounds etc and within minutes, the conversation is flowing. What you said about vulnerability really resonated...Something about eating together, knowing that in that moment, we are each of us hungry and will each of us satisfy a desire - together- is so bizarrely intimate and disarming that we readily offer up a small something of ourselves. During these meals, myself along with these perfect strangers have shared facts of our lives pertaining to our grief, joy, hope etc alongside more mundane details "and what part of London are you from then?" I never really thought much about why these spontaneous encounters felt so special until you articulated so brilliantly the connection between vulnerability and the knowing that you'll never see these people again!