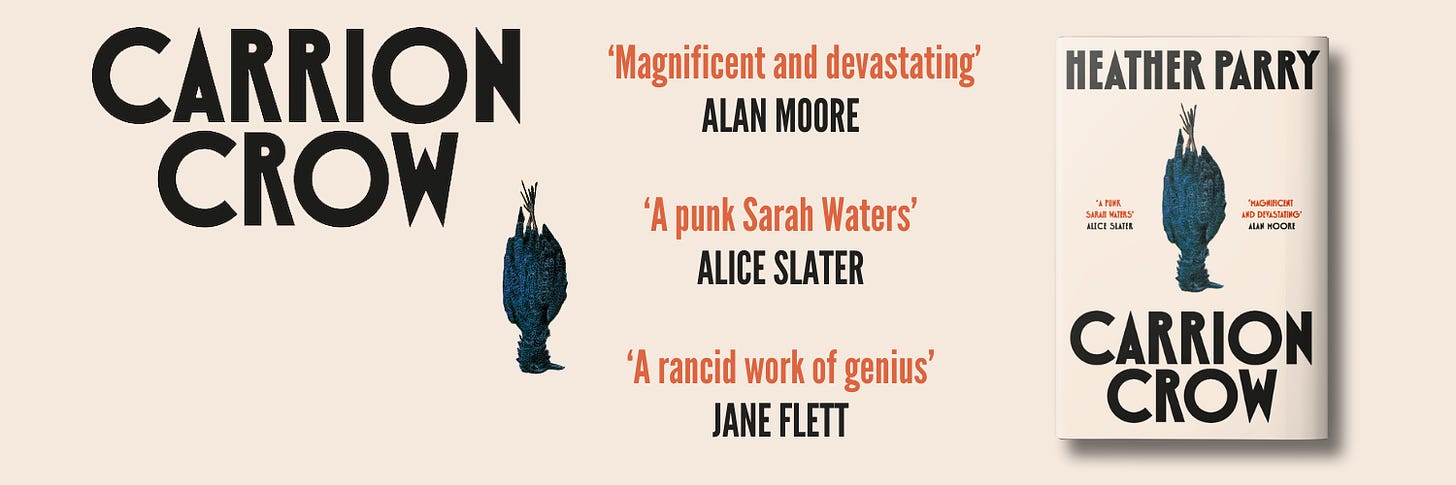

My new novel Carrion Crow is now firmly OUT in the world (I’m fine, I’m FINE) and I’m taking it on tour! I’d love to see you at one of these events. Tickets can be booked at the links here.

Let me walk you through how my year has gone, writing-wise. There is a point behind the next few paragraphs, I promise.

In January, I spent the month writing a book. Well—finishing a book, one that I had started back in 2021, which hadn’t quite found its footing. Well—not finishing, really, because I’ve still got a couple of stories to go, and even when they’re done I’ll put it in a drawer for a month, and then it’ll be workshopped, and re-edited, and then it’ll go to my agent then my editor, when the proper editing will begin, if it’s accepted. So really, all I’ve done is slightly progress towards finishing a first draft, about three and a half years after I started it.

To some extent, this is frustrating, as I had spent the last two months of the year doing all my Jan/Feb work in advance, so I could really focus on this project, really getting lost in it. But the problem was that I had convinced myself that the book was something other than what it really was: by the time it came to work on it, I spent two weeks having a series of breakdowns because I just couldn’t do it. The restrictions I had placed were too tight. My idea of it was all wrong. Only when I had undone them—over a lot of cold walks and pathetic wailing—could I really start to progress. Then, after some successful writing, I realised what I needed in order to finish was not to be working on it, at least not looking directly at it. I needed space for ideas to come in. There is such a thing as thinking about a project too much.

In February, with this project and an unfinished novel looming on the horizon, I drove through Glencoe on the way back from a weekend away with a pal and suddenly had an idea for a novel. I went home, cleared my decks and subsequently wrote 30,000 words in two weeks (I am extremely good at meeting daily word counts; this girl needs deadlines to function). I was so caught up in the idea and the excitement of newness that I barely realised I hadn’t a fucking clue what it was supposed to be doing or saying, and that what I was writing was a series of completely unconnected half chapters, because I didn’t really know who my characters were, I hadn’t thought about the layers of meaning needed, and my idea was as shallow as a fresh puddle. Of course, I ground to a halt after a fortnight. I tossed the thing as quickly as I’d started it. It was distinctly under-considered; I had not thought about it enough.

Part of the reason I struggled in January and February is that I was trying to write in the weeks before publishing another novel, which is simply an insane choice (as any writer will tell you, you might feel okay in the weeks before publication, but on a cellular level you are simply not). The major reason, however, was that I had not timed things right. For me, the actual process of sitting down and writing a novel—which happens in a relative whirlwind, with lots of subsequent resting and revisiting—has to occur at the perfect peak of my interest, when I have done enough research and have enough of an idea who my characters are and on what journey I want them to go; I need not only the three-act structure and the start and a vague idea of the end, but a loose map of the middle terrain. But I also need to not have planned so much that there is no freedom for those characters to find themselves on the page; if I have too much of an idea, we’re all trapped, me and those characters. I need to pitch the process of actually writing the novel at the perfect point between underthinking and overthinking. Otherwise, I might well be writing, but I will be writing a load of shit.

I am telling you all this, tediously detailed as it is, because I know many of you are writers, some unpublished as yet, and I know that a lot of you will have internalised the bizarre message that if you are serious about writing you must write every day of your life, that projects will flow out of you in unbroken months and everything you write will be golden. You will have unshakeable confidence, you will know what you’re doing. This, as any published writer will tell you, is simply not how it works. And I think it’s important that we talk about that fact.

When I was a fledgling writer, I was terrified by the Murakami/King tales of writing schedules: waking up at 6am to write for six hours come rain or shine, 365 days a year, then running a marathon (or doing a ton of coke, if you’re 80s King). Media outlets love to write about this kind of thing, because it presents writing as a skill only available to the most insanely committed, the magical few (men) who have pure commitment and endless time, as if the writing process is the 37th chamber of Shaolin. This, I thought, is what you need to be able to do if you want to be a writer. This is how you do it.

I have come to recognise that this—the idea that a writer, if they’re serious, has to write every single day—is perhaps one of the least helpful myths in a cramped sea of bad writing advice. It might apply to a handful of writers, or even a sizeable minority—but it is simply not how most of us work.

Advice that doesn’t apply to you is easy enough to discard, even if that realisation only comes through long painful months of trying and failing to meet its demands. But what is so terrible about this particular advice is that it puts the focus on the work of writing on the production of words rather than the consideration of them. It is actually quite easy to find time to write, if you’re just writing for writing’s sake; most of us can find an hour here or there to just type up to an arbitrary word count, even if we do it while sat on the toilet. A decade of building a writing career has taught me that it is the space to think which is most valuable for a writer: the daydreaming, the non-scheduled brain time, the reading, the researching, the flights of fancy, the time to drop into deep realisations that will eventually be expressed in what you do write. Haruki Murakami might well have several hours every day to think about his projects while he is running his marathons, but most of us do not. Most of us have to work, or raise kids, or support other people, or care for loved ones, and so all that non-writing time is taken up with thinking about the rest of our lives. So where does the thinking about writing, about life, occur? It simply doesn’t. What we end up with is a lot of words and no time to actually think about them. And on top of that, a lot of guilt.

I spent so many years thinking that if I was ever going to get anywhere with my writing, if I was ever going to have a writing career, I needed to be getting up at 6am and sitting at my computer for a minimum of six hours, writing no matter what. But here’s a thing about me: I fucking hate getting up in the morning. In the winter, I despise it especially. It is cold in my flat—a top-floor tenement with three external walls—and in the winter in Scotland it is dark until eight thirty or later. Where I want to be is in bed, possibly with a coffee and a laptop but most likely asleep with a cat on or near me or my partner wrapped around me. I can drag myself out of bed if necessary in the dark, but it’s miserable, and my brain is tired, and its not conducive to productive work in the first four hours of the day. I might as well be in bed.

I also can’t work so doggedly to a schedule. Trying to make myself produce all my day’s work before noon is a fruitless endeavour. When I write, I DO have to give myself strict word counts every day, but I might need to sit there til 11pm or later to get them done. I need that time. If I try to write 1000 or 2000 or 3000 words by noon, I will just write a lot of bad words that will end up being deleted. I need the right balance of sustained pressure and freedom to think, and I can’t achieve anything that productive by noon on any day. And a marathon? I hate running more than anything. I have done a half-marathon once in my life, and a few 10ks, and every minute of them was miserable. Every few years I force myself to go on a single run, convinced that this is what real adults do. And by the end of the street I want to kill someone, so I stop.

The other extreme at the end of this advice-spectrum is the people who manage to achieve some degree of writing every day despite not really having any time to do so. I would love to be one of those people of immense fortitude who can sit down to write after a day at a 9-5 job, or a day looking after kids, or a day doing whatever life throws at you. Those people who manage to write a book in twenty-minute sessions every day on their phone on the bus home from college or uni or work. This has never been the case for me. Not when I was working briefly at a regular office, nor when I was working part-time remotely, nor when I have been full-time as a freelancer, juggling a bunch of different projects. I simply can’t do it. I don’t have that kind of brain.

I spent a long time self-flagellating because of this. These people can’t really do it either, but they HAVE to, I told myself. You surely can too, if you just stop being a fucking baby. But it’s just not the case. Just as surely as I will write boring shit if I do the chapter-by-chapter planning that works so well for other people, if I try to write in miniature shifts over six months or more, I will simply lose interest. I need to build everything up, get to the point where I’m desperate to write, then do it in a oner. This realisation was a long time coming. It is, perhaps, an odd writing process. But it is, inarguably, mine.

Here’s what I have realised over the last nine or so years since I first finished a long first draft: every writer is different, just as every brain is different. There is no moral loss in not being the kind of person who sits down every single day and writes. In fact, I’d venture to say that some of those people just end up writing as much shit as I do, in those circumstances. We all do, and you have to, sometimes, to get to the decent stuff. But for me, that would be far too much bad work—it would discourage me, and actually push me away from the process.

I can only really fiction write decently when I have something to say. When I have built up my little brain-nest with the requisite stuff: inspiration, annoyance, rage, facts, character bits, imagery, self-belief. And then, it all has to come out in a single intense period, four weeks or six weeks, before I lose the concentration and confidence and focus.

In these periods, especially when they’re in January, I find it helpful to have a bunch of supplementary projects on the go, low-stakes ones about things I already enjoy, challenging in different ways to the fiction project but similarly creative. These usually involve art and food, given that I can’t read much fiction when I am writing it. This time, my non-writing creative brain was mostly led by Wendy Mac’s 30-Day Drawing Challenge (a habit I picked up last year and really enjoyed), along with a foray into gouache portraiture mainly learned from YouTube videos by generous artists, and an exploration of my own cookbooks formed by my discovery of the well-worth-the-money website Eat Your Books—as well as the gym, in the evenings mostly, and a ton of walks, with either a podcast or my own thoughts.

Every day, there was some sort of fitness/movement, a selection of two meals from books I already owned, 10 minutes on a drawing challenge and maybe an hour with a YouTube video and some paints—alongside a lot of writing and thinking about writing. This left me challenged, satisfied, creatively engaged, well fed, satisfied by using up all the food in my fridge, filled with new flavours, tired enough to sleep well and stimulated enough not to be seeking out new stimulation through scrolling on my phone or creating drama for myself. I can’t keep this up for more than four or five or maybe six weeks—and that’s okay. That’s how I work. I’ve figured it out by now. And when you’re a writer, that’s half the challenge.

When I speak to creative writing students, those who are working towards careers as novelists, I often tell them the best thing they can do is to write a novel and to throw it away. I say this partially because you can get too hung up on the first novel you finish, and sometimes you can get so stuck there that you never progress, but really what I am telling them is that they have to actually write a novel in order to work out their process, to find what works for them and what doesn't. And if you’re a writer, I would say the same. Perhaps you are one of these people who can sit down at a strict schedule every day of the year and produce brilliant work. Perhaps you’re a bus-commute writer, managing only a few sentences each day but building a gorgeous manuscript in those bitesize bits. Maybe you’re like me, a burst-writer, or maybe you’re something else altogether. But you won’t know until you actually do it, until you try all these models on and see which one fits. Writing is not one size fits all.

There is one thing that applies to all writers, though: You don’t have to write every day. But you do have to think. And, ideally, to read.

My new novel Carrion Crow—a dark, physical book that ‘deduces an unutterable Gothic horror of class and gender from the pages of Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management’—is out now, and you can order it here:

Loved reading this. As a chronically ill writer who writes from bed more often than not, at an erratic schedule that sometimes produces great volumes of words and sometimes only a trickle, it's deeply frustrating seeing those articles floating around about writing every day, as if that's the only way to do it, to prove that you're committed.

As you said, "what is so terrible about this particular advice is that it puts the focus on the work of writing on the production of words rather than the consideration of them."

Writers aren't production lines. Or we shouldn't be, anyway.

Also: deeply excited about Carrion Crow!! 🖤

Thank you so much for speaking up!!!

Writing every single day and hitting those mythical 1000+ words every time is such a debilitating myth that caused multiple writers, beginners and seasoned ones alike, so much anxiety, impostor syndrome and heartache that I can't even bear to start on that.

And when does the thinking about writing happen? When indeed.