Listen. There was a time in this country when you could travel between Manchester and London on a train for fifteen pounds and get a guaranteed seat. There was a time where you could pay thirty pounds for the same journey, and you’d sit in first class, and you’d get a free meal and free wine (unlimited), and the train would go on time, and was hardly ever cancelled, and wasn’t rammed full of people even if you weren’t in first class, and you wouldn’t get charged an inordinate amount of money if you couldn’t lay your hands on your ticket—which was printed from a machine at no extra cost, meaning you weren’t reliant on a phone battery designed specifically to be unreliable and train WiFi that barely works. You could get on a train in Manchester, and you could show up in London on time, fully fed and a bit drunk, having paid only thirty pounds for the service. I know this because I was living in Manchester and dating someone who lived just outside London, and I did this journey many times between 2005 and 2008.

This experience was available to anyone who had thirty spare pounds. All you had to do was book six weeks in advance. That same journey, in first class, is now £144 (one way) booking the same time in advance. The journey is two hours long. A one way from Glasgow to London on the same date is £108 minimum if you can’t travel after 2pm. That journey is four hours long.

Some will say that those prices aren’t too bad. These people, I’ve come to believe, are either a) idiots or b) so captured that they cannot imagine a different reality, even though this reality existed only a decade and a half ago.

A few years ago, I woke up on a Saturday morning thinking about emergencies, and checked how much it would cost for me to get to my home in Glasgow to my parents’ home in Sheffield that day, with my partner, on an open return. The cost was over £900. The same year my friends, over from New Zealand, wanted to travel from Swindon to our place on short notice to visit. Two tickets return, and a free child? It was £1000. One thousand pounds.

The train nerds are right. The system is fucked.

It didn’t always used to be this way. In fact, the British rail system used to be a leader. We’ve had a national rail network in this country since the 1840s, though there were over a hundred private companies running the trains. By the 1850s, most towns and villages in the UK were connected by rail, thanks to the labour of a quarter of a million ‘navvies’ who laid down 3000 miles of track; in the decades after this would be increased to 13,000. As early as 1844, nationalisation of the rail system was put to parliament—and, of course, rejected. But it did spark state-level protections around safety and also inclusion for the working class: provision of cheap, covered services with strict rules around the maximum cost. The Railway Regulation Act of 1844 legally mandated:

the provision of at least one train a day each way at a speed of not less than 12 miles an hour including stops, which were to be made at all stations, and of carriages protected from the weather and provided with seats; for all which luxuries not more than a penny a mile might be charged.

Though even a penny a mile was beyond the reach of many people, this law, and the new expansion of the railways, had an enormous impact on the lives of the working class. Suddenly they could travel across the country for both work and leisure. By 1883, the overcrowding of the cities fed a desire to move workers out into new developments in other parts of the country, which of course required more public transport; the Cheap Trains Act of that year was the beginning of real worker’s trains services and a massive increase in the number of suburban services—but not without pushback, as the rail companies had already stopped being profitable.

In the first world war, the whole rail network was brought under government control, but increased calls to formally nationalise it met a dead end. By the 1920s, almost all train companies were conglomerated into the ‘Big Four’ who effectively worked together as one company during the second world war. But real nationalisation couldn’t be resisted for much longer. In 1948, British Rail was created, and the railways were, formally, nationalised.

If you talk to anyone over 65, they’ll tell you that British Rail was a nightmare, but you have to take that in this context: they are now retired, so get rail tickets at a discount and can probably travel whenever they like, and are unlikely to have been, lately, stranded in Preston for six hours having paid £150 for the privilege, completely missing the thing they were travelling for in the first place. It also has to be taken in the context that the British government was so desperate to make the railway profitable—rather than a subsidised public utility—that they carried out an unbelievable act of public vandalism in the 60s. The British Rail of conversation is not the company of the late 40s, but of the 60s and beyond.

When British Rail was established, though, it was a success: rail use increased, and it did become profitable. But expansion and modernisation in the 50s cost a lot, and yet did not encourage people onto the trains and out of their cars in the numbers that were hoped. And so the British government turned, in the early 60s, to an engineer called Richard Beeching.

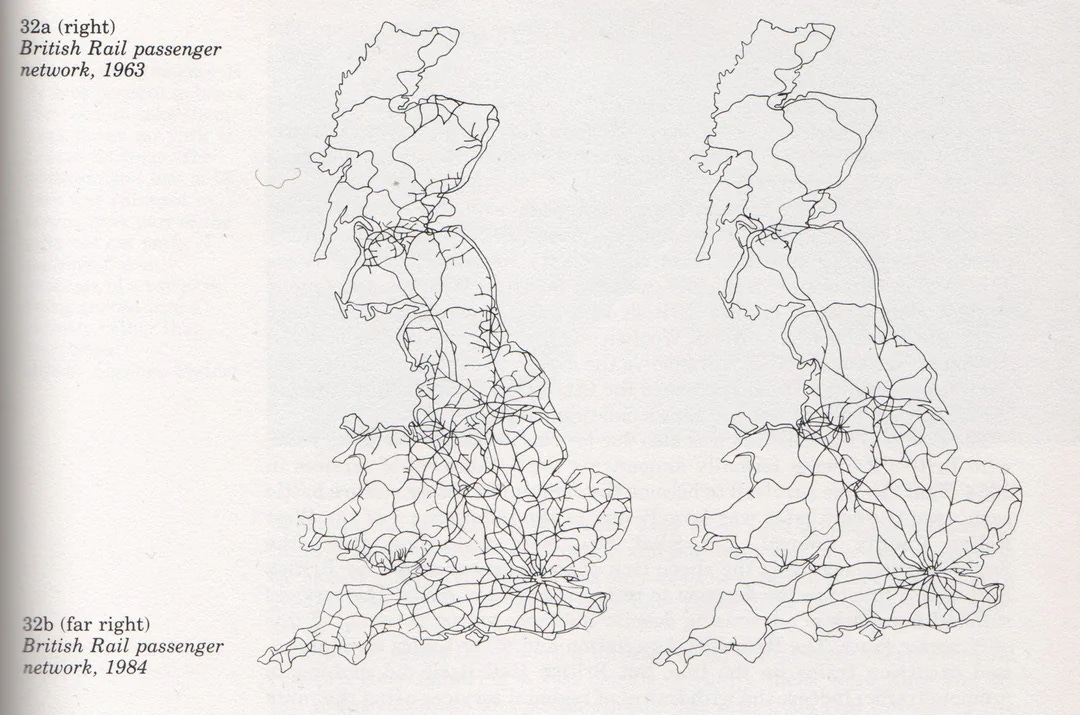

As chair of the British Railway Board, tasked with the job of making the railways profitable again, Beeching wrote a report in 1963 called The Reshaping of British Railways; the first of two reports, this called for a severing of enormous parts of the rail network, predominantly those connecting villages and market towns, but also some major lines between cities. Overall, the two reports recommended that some of the ‘trunk’ routes be invested in, but that 5000 miles of the railway (30% of the total) should be closed, along with 2363 stations (55% of all stations in the country), and that almost 68,000 workers should be fired. Though some protests and pushback kept a stations open, the vast majority of this decimation was carried out. It was, of course, extremely unpopular with the people of the UK. If you talk to anyone knowledgable about the state of the trains these days, you will almost certainly come back to the topic of the Beeching Cuts.

Into the 70s, passenger numbers decreased hugely; in 1972, the system was sectorised, and one sector—InterCity—became very profitable. But it wasn’t enough to resist the assault of neoliberal economics and the anti-nationalisation fetish of the Conservative government. By 1997, Prime Minister John Major had completely privatised the railways, setting us on the path to the experience that we know now: insane prices, terrible customer experience, and a siphoning off of profits to line the pockets of the rich.

But worst of all, all these things cost us, as a country, more than they did before. By 2019, government subsidies to the rail industry were three times what they were in the late 80s. Between 2022 and 2023, the British tax payer gave £4.4 billion in subsidies to the companies who run the trains in the UK. Most maddeningly of all, most of these companies are actually European state railway companies: TrenItalia, Deutsche Bahn, Nederlandse Spoorwegen. The British government, it turns out, is fine with state ownership of the British railways, as long as the state in question isn’t us. Meanwhile, fares are so high that two specific short journeys now work out to over £12 per mile. We are paying twice for these railways, so that the stakeholders of predominantly European companies can rake in wild profits; realistically, we are subsidising brilliant and affordable European state travel for our neighbours. We are bankrupting ourselves to take the train—so we don’t have to drive or fly, both cheaper options that are completely destroying the planet—despite knowing that paying £250 to get to Bristol and back doesn’t actually mean you will arrive on time, or that the service will go at all, and that you may well not get a seat the whole way; you might end up stranded, paying out of pocket for a hotel, by weather, or by the endless rail strikes by which workers are trying to force their employers to make the railways safer and pleasant to use. Many places in the UK remain without rail service, and in the north this is the worst of all. This whole situation, quite frankly, is taking the piss.

I hate the person I have become when it comes to the trains. I actually love train travel. There is something wildly chic about getting on the train in London and getting off it in Paris. I would love to take a sleeper up to the north of Scotland, but of course cannot really bring myself to pay the extortionate cost. I hugely value being able to get from the city centre to my flat in ten minutes, but hate that there’s only one or two services per hour after 6pm. I basically exist in a state of perpetual rage at the state of the railways. It’s not good for my health.

More than this, I hate the country we have become, when it comes to the trains. We fetishise—correctly!!— the railways in other countries. We go on holiday to Japan and see the roomy and fast trains that go between cities, seemingly never full, and talk about the wonder of it. We jump on the train in Milan and step off in Florence and talk about how lush it is. We share, endlessly, photos of steam trains on our own disintegrating viaducts. We know it can be better, and we know that it should.

And yet. If you are stupid enough to tweet about having to remortgage your flat to travel 200 miles in the United Kingdom, as I am, you will be subjected to the following:

someone saying you can actually travel for a quarter of the price, if you have one specific railcard that isn’t available to anyone between the ages of 30 and 66, and if you travel a very popular line at a highly unpopular time, and if you are flexible with your travel days but also have the foresight to book at some unknowable point ahead of your travel date which is measured in months and not days

someone telling you you can’t compare it with the cost of driving a car, as the car incurs wear and tear from being driven as well as the petrol cost

someone saying you can at least work on the train, which can only be said by someone who hasn’t tried to work on a British train for the last decade

The last point here really sticks in my craw: currently I am writing this on a train, on a 7-hour round journey (now 8 1/2, due to a late arrival and missed connection) which cost £80 return purchased well in advance, and the train is rammed, and I have got a seat, but the fold down table in front of me a) folds my laptop down in such a way to be unworkable (literally you cannot see the screen nor type) and b) is about eight inches wide. I got a table seat yesterday, on the outward leg, but the tables are both tiny and cut on an angle, so you actually cannot get a (small!) laptop on it if someone else wants to use it at all. The WiFi is so bad it cannot load a single browser page. I am writing this on a Word doc, and tethering from my phone to research things, and working hunched over my laptop which is on my knee, which will destroy my back by the time I get home. I am in my thirties and able bodied and relatively flexible and a good traveller, yet this journey will still fuck me up. You cannot reliably “work on the train” unless you spend hundreds of pounds to be in first class, and even then the whole booking system might be fucked and you might not get a table, or you might be shunted onto a rail replacement bus, or they might declassify the tickets and you end up in the same situation as everyone else, or standing the entire way. Why are we simping for the overlords of the rail system? Why are we telling ourselves lies?

Here’s the thing: even if you don’t care about trains, or you don’t think that the current system is completely insane, you’re going to have to soon enough.

We can’t talk about climate change without talking about public transport. Our current rail system is forcing people into their cars, not out of them. I know, because I am one of these people: I didn’t have a car for the first fifteen years of my driving life, and now I have one. I travel around the country a lot for both pleasure and work, and so much of it remains unconnected to rail lines (or even a bus service). If you have always lived in a city, I think you struggle to understand how many people simply do not have access to public transport, how many places are inaccessible apart from via a car—thanks, often, to the legacy of the Beeching Cuts. Rural communities rely on cars. In the north of England, which has been underfunded compared to the south for decades, taking public transport between two major conurbations often doubles or even triples the length of a journey, compared to driving. Add in the highlands and islands, where ferries and flights completely fail to serve the communities they’re supposed to, and suddenly that’s a lot of people isolated, or forced into cars, or both.

And it’s not just around travel in the UK. While it remains cheaper to fly to Europe or even India than it is to get a train from one end of the UK to the other, people are going to continue to fly away on holiday instead of staying closer. Even if you have the money to travel to Europe via the trains, which often costs hundreds of pounds and several days—and if you’re abled bodied, flexible with travel dates and travelling without kids or the elderly—it is hard to find employers that will give you additional holidays for slow travel. How many people are going to take four days off their annual holiday to struggle across the UK then onto the continent with their whole family, having spent hundreds of pounds to do so, when they could just fly for a quarter of the price and have half a week more sitting on a beach, trying to shake off the endless stress of living in the UK? We need to make it easier and cheaper to do the right thing, not more expensive and infinitely more difficult.

The climate is collapsing, and we need to change things now. We need to stop flying and stop driving, yet we are being forced to do both because the trains are so awful. What we need is for the railway to operate as a massively subsidised public utility that operates for the sake of the people that use it, not millionaire stakeholders in this country or others. And the worst thing is that if you care about all of this—about the climate, and about fairness of access, and about allowing the working classes to enjoy freedom—then you then have to give a shit about economics as well. I’m sorry. I hate it too. But all left wing roads lead to this.

At the end of last year, the RMT stated that £31 billion has leaked out of the system in the three decades since John Major’s privatisation binge, mostly into the pockets of shareholders. But they also offer a way that this can be changed, and fares can be brought down:

Renationalising the railway and creating a single, integrated publicly owned railway company would save around £1.5 billion every year which could be used to cut fares by 18%, helping to encourage more people back onto Britain’s railways.

The RMT is not alone in saying this; even Labour, in its current insipid, neoneoliberal, virulently antisocialist phase, claims it will nationalise “most of” the rail network within five years of coming to power, although this is both too slow and promised by a man who has rolled back on every campaign promise he’s ever made, so you’ll excuse me if I dismiss these as the cynical claims of a historical liar.

But even in the above examples, the parameters of debate are being set by the structure of austerity, by the framework of neoliberalism. The parameters of the discussion are affordability and savings. This is the only way we can operate, in this country, since Thatcher said that a national economy works the same as a household budget, and in doing so destroyed the ability for regular people to engage in progressive discussions about broader economics. Even the Labour Party, in its bid for power, constantly talks about there being no money left in the public purse. But if you really care about these things, you have to understand this: this is not how the economy works at all.

I am not an economist, and I won’t try to make you into one either. But I will implore you to read up about Modern Monetary Theory, and the deficit myth, and the truth that national debt is not the crisis we think it is; most governments are in debt (in large part) to themselves, and when money goes out of the public purse on services and jobs guarantees and benefits, it does not disappear; it goes into the pockets of the public, who then spend it in the system. When it is given to shareholders, conversely, it is taken out of the system, often to tax havens where it exists beyond our governmental remit. But money spent on the people is different. Money does not cease to exist when it is spent at the national level. We can, in fact, control where it goes, and we can create it too; we often do. People much smarter than me insist that governments have a lot more financial leeway than they would like us to know. I ask you to Google what Marx said about the rate of profit in capitalism, and look at what is happening around us now. At the very least I ask you to read up about how austerity has never worked and cannot get us out of the hole we are now in. You don’t have to believe in MMT to know that we need to spend our way out of this mess, like so many other countries have, like we have done before now. We need to nationalise our industries, and look into UBI, and look into jobs guarantees, and stop letting shareholders and corrupt politicians rinse billions of public money out of the system in order to consolidate their already massive wealth at the expense of the regular people who have less and less and less everyday: at the expense of our social support system, and our pensions, and the betterment of our societies, and the saving of our planet.

The Better Transport campaign calls for an investment of £4.8 billion in our railways, to bring half a million people within walking distance of a train station and allow 20 million additional passenger journeys per year. The concept of renationalisation is hugely popular, consistently sought by over half the population, regardless of political leaning. I implore you to get pissed off about the railways; I beg you to get so mad you can’t contain yourself. We deserve clean, green travel that runs to the many corners of this country. We deserve jobs that pay well, and are safe, and give us a sense of value in our work. We deserve train journeys that are not only affordable but cheap, and we deserve a glass of wine and a free delicious meal while we’re on it as well. We could afford all this, if we wanted to. We can, and need to, do better than this.

I found myself nodding along to all of this. I live in Cornwall and recently I've found myself flying to London when I need to travel there for work because it is literally half the price. And because all of my recent journeys on trains have been delayed/cancelled/extremely squished/or I've had to stand for hours because seat reservations have gone wrong. I love travelling my train too, and think flying is awful for the environment but as well as costing less, it's quicker and more reliable.

This is so true - and really timely. It also ought to be possible to just turn up and buy a ticket, without swingeing penalties - life doesn't always book x weeks in advance: and, anyway, what about spontaneity? (And catching that train to Paria ri meet a friend for lunch and catch an exhibition...ha!)