Having lived in a few different countries, and as a fan of a holiday, I am acutely aware of several facts: 1) it is really easy to go abroad for a few days, drink a lot of wine and do no work, and then decide that that place is much better than where you live. In fact, it’s almost inevitable. 2) Every country has its issues. 3) There’s nothing innate about the politics of a place, which can change with every election, or change not at all, or change very abruptly in response to the organisation of its people outside of the electoral process. 4) Nowhere is perfect.

However. It is next to impossible to visit other cities these days and reflect on what they have, compared to what we, in the UK, increasingly do not have. These things in particular came up on a recent trip to Bordeaux: a clean and functional tram that runs from the airport to the city centre for just €1.80. Beautiful, well-maintained parks. Ferries that run regularly, cheaply and on time (Scots, look away now). A huge, ridiculously high-quality food market populated by tradespeople and producers, not chain outlets. A massive converted former military barracks that houses all kind of start ups, small producers, a bookshop, a skate park, community groups and an affordable organic cafe. Outdoor space in public use. Facilities widely inclusive of disabled people and families. Library outreach programmes in the public parks which not only brought musicians out to play for kids and their carers (and anyone else who wanted to stop by) but also had movable book racks, with hammocks which could be tied to trees to create “reading nooks” for the kids. I mean, just look:

I am not trying to say here that Bourdelaise politics, nor the wider French political system, are perfect, or even good; what I am trying to say that when you go away from the UK for half a minute it is startlingly clear what an enormous pile of shit we have grown used to—and that our politicians can get away with promising us absolutely nothing because of it.

A few weeks ago I went walking with a Belgian friend. She told me that if she were in Belgium, and lost her job tomorrow, she would receive 65% of her gross wages for three months. After that it would be 60% for up to a year, then 42% for the next year. I have since done some digging around, on the topic of social support systems on the continent: in Bulgaria, maternity pay is 90% of your income for almost 59 weeks (13 and a half months). In Norway, it’s 80-100% of your salary for 49 weeks.

UK maternity pay is among the lowest in Europe. We have the worst unemployment benefits in Northern Europe. Ours is the third highest retirement age in all of Europe, and the government’s own data says that ‘The UK devotes a smaller percentage of its GDP to state pensions and pensioner benefits than most other advanced economies.’ We’re 10th out of 15 for publicly funded health spend per capita. German bank N26 put together a European liveability index, comparing things like wages, the cost of living and the general happiness of citizens: the UK came dead last. Yet we are the second richest country in Europe.

And it’s not just social support systems or transport or libraries. In the UK - and especially in Scotland - we have some of the lowest public investment in the arts in all of Europe. As I’ve written about before, the City of Berlin’s culture budget for 23/24 is about £840 million. The Creative Scotland annual grant-in-aid from the government, to cover the whole of the country, is only £68.5 million as of 2024. There are around 2 million more people in Scotland than in Berlin. So why are we supposed to be content with less than a tenth of their arts funding? If we are so rich, where is all the money going?

Of course, we all know where the money actually goes: to the top. The UK recently fell to its lowest position on Transparency International’s corruption perceptions index, which “ranks countries by experts’ views of possible corruption in public services”. Via various corrupt schemes, and tax loopholes, and capitalism, the rich get richer and the rest of us suffer. And, of course, via war; public money is spent on arms, and on military aid, and what this means is that arms manufacturers and their investors grow richer. In 2022, the UK had the highest military expenditure in western and central Europe, at $68.5 billion. Earlier this year both Rishi Sunak and Keir Starmer pledged to raise UK military spending to 2.5% of GDP; for context, in 22/23 our spending on education was only 4.2% of GDP, a number that is falling rather than increasing.

Keir Starmer, the first non-Tory prime minister in 15 years, has committed to sending £3 billion a year to Ukraine indefinitely. In pretty much the same breath, his chancellor Rachel Reeves set about limboing under our already floor-level expectations by immediately announcing that she would start means-testing the winter fuel payments, making sure none of those pesky old people get their measly £300 to help with heating unless they REALLY ARE on the brink of freezing to death. There’s a £22 billion funding hole, she says, and that will need to be fixed via some “tough decisions”. The sensible people are back in charge, and they know what’s good for us.

So far, then, our new Labour government has promised us two things: more war, and yet more austerity, the economic approach which has massively diminished the quality of life for Brits for the last decade and a half. And you’d think, after all this, that the issue would be solved, no? But it isn’t, because austerity does not and cannot work. Even the IMF says austerity cannot work. All prominent economists say it cannot work. But here is our supposed saving grace, the supposed alternative to the Conservative Party, and all they have to offer is more of the same. We cannot, it seems, ask for better than this.

I am not an economist and don’t claim to be. But what I do know is that economics used to not just be the preserve of the elite; workers used to have a much better understanding of it, and that was changed on purpose. There’s been a concerted effort to cover up how the economics of a country really works, since Thatcher started insisting that a government’s finances work like that of a household. They, of course, absolutely do not.

Neither you nor I, when faced with a budgeting issue, can print our own money (well, we can try, but it wouldn’t go well for us). The government can and does constantly print its own money. In fact, even banks invent money all the time; they loan out far greater amounts than their ‘reserves’, creating money when that is paid back into the system. A government absolutely can create money; the argument has always been that when they do so, this causes a massively high spike in inflation. But many economists argue that, again, they do this all the time, and in fact whether or not this causes an inflationary spike is down to a country’s productivity and output.

Not even government debt can be thought of in the same way as household debt. For a start, about a third of the UK’s debt is a debt to itself. I won’t attempt to explain to you why that is; instead I’ll point to Richard Murphy, who does great work around building a more fair and ethical economy. Even the concept of “taxpayers’ money” is wrong, used more to enrage you about the perceived misspending of your money than to describe the situation accurately. In Richard Murphy’s words:

The fact is that every time the government spends money - and remember, it spends a trillion or so pounds a year - it does not go to the Bank of England and say, “Hey, is there any money in the account? Can I spend it today? Or should I actually hold back for a day or two until some more tax is paid?” That is not what goes on.

Instead, Parliament authorises the Government to spend by the passing of a budget. Once the budget has been passed, the spending is legal and it can therefore take place. And the government then goes along to the Bank of England, which it owns, and says, “We now want to spend this money, which Parliament has approved, therefore please extend the credit to us to let us do so.”

And so, the Bank of England, quite literally, marks up an overdraft for the government every morning, as it starts to spend, and lets it go spending on whatever it wishes because it is a bank and it can extend credit because the government has made a promise to repay it, at least technically. Now, that's what happens, therefore. Every time the government spends, it creates new money.

Just like a bank does not lend out depositors' money, the government does not use taxpayers' money to spend. This idea that taxpayers' money is used to pay for government services is wrong. It is complete and utter nonsense. It is untrue, a fiction, a falsehood. I don't mind what else you want to call it. It is simply not correct.

He goes on to explain that tax collected then goes to repay the money that was ‘created’ for the government to spend (but likely not all of it), avoiding inflationary spikes. If we look at it this way, what becomes important is not how much money the government is spending, but what it is spending it on.

For example: if a government gives £100 million to some shady MP’s offshore company for some PPE that never works, not only is that £100 million that has not provided anything concretely useful, it is also £100 million that will be largely taken out of the economy through a series of loopholes and dodgy accounting; most of it is simply gone.

However, if the government spends £100 million on a policy of productive job creation - let’s say, on jobs that make solar panels, for instance - that’s £100 million that is going in to the pockets of workers (of course some would go on parts, etc, but let’s just say the whole amount is going on wages for ease) and those workers are outputting something useful and valuable. That £100 million does not go out of the system; those workers use it to pay for things. They go to restaurants and buy food, which pays for the wages of other workers (and also for food products, rent, utilities etc. as well - pin this thought, we’ll come back to it later). They spend that money in their local economy, and they pay some of their wages back in tax, to repay the ‘loan’ that created the money in the first place. The restaurant that they eat at pays taxes; the staff at the restaurant pay taxes. You can see how it works.

And back to that pinned thought: if the food that the restaurant buys comes from local farms, that money stays in the local system. If it rents its storefront at a subsidised rate from the local authority, the money stays. If the utilities are paid to a publicly owned company, a nationalised utility company, it stays in the country. More of it comes back to the government in tax. However: if the food, rental space and utilities are all massive international conglomerates, the money goes out of the system again: to shareholders, here and abroad, who are less likely to pay tax on it through various schemes, to offshore accounts, etc. This is why it is much better for the system generally to work locally, for buildings to be owned by the local authority rather than private landlords, for utilities to be nationalised.

There’s a lot more to the situation than this - trade and trade deficits, the price of things like oil, the issuing of bonds - but this, I think, is a good first step in understanding how the economy really works. The government can’t just print and spend money with no thought to how it will be ‘paid back’, but government debt is not the massive issue we believe it to be (most governments have to be in debt to themselves, to some degree). The bigger question is what the government is spending it on - or rather, who they are giving it to. Are they giving it to citizens, through jobs or benefits or stable housing or healthcare, which invests in people, keeps money in the system and stimulates our own economy - or to massive international companies, headed by billionaires, who will remove the money, not pay tax and extract yet more from both people and environment?

This is, of course, why governments don’t want you to ask this question. They are giving it to the rich.

You can also see from this why lowering spending - austerity - does not work. It is the opposite of stimulating the economy; it is shutting down the economy. When people have less, they spend less; the economy stops being productive. The costs of running the country also go up in this model; people’s health worsens when they are poor, or when their living conditions have diminished, so they need more care. That care is increasingly privatised, so when the government does spend, the money goes out of the system. When the system is nationalised, the government itself recoups any profit from the spending. But when it is privatised, out it goes. The government spends more trying to cover over the issues caused by its low spending. And out the money flushes - out of the system and into the pockets of those who own the private companies: the rich.

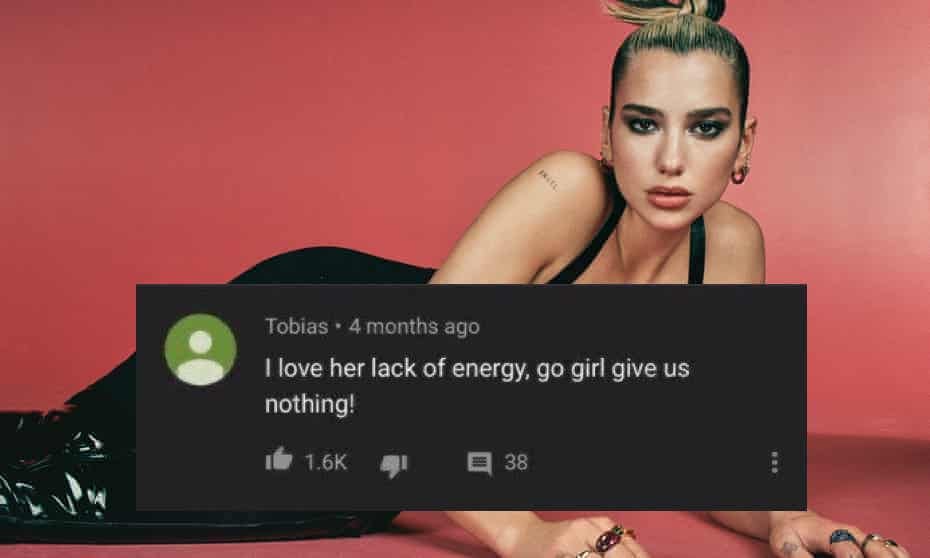

All this is to say that giving us nothing is a losing long-term position for the government. They chase this idea of lower spending even though it is keeping us on an economic death spiral, overall; it is part of the endless transfer of public money to the private sector. They do this because of their neoliberal ideology but also because they will, eventually, personally get kickbacks from the companies or individuals whose pockets they lined when they were in government; it’s why both Tony Blair and George Osborne went to ‘work’ for banking organisations after their tenures, for over half a million quid in both instances. They have to appease the rich while in power, because the rich increasingly decide who the country votes for; look at the newspapers, at the way they destroyed the socialist project in 2015-2019. Rupert Murdoch’s News UK, part of NewsCorp, controls 32% of weekly newspaper circulation; DMG Media, headed by billionaire Viscount Rothermere, accounts for over 38%. They want their interests protected, and they control public opinion, so both Labour and the Conservatives pander to them if they want to get in. The system feeds itself. And the rest of us continue to suffer.

After war, governments have always understood that they need to spend to rebuild, to stimulate, to stabilise. Governments also know this now. But they will not - for all the reasons outlined above. The facts are that they could give us all the things we fetishise when we go to other countries: cheap, functional public transport. Rent controls or subsidised housing. Free education. Strong disability and unemployment benefits that preserve dignity for all people. Good state pensions and elderly care. A health service that doesn’t just attend to emergencies but helps us maintain and support our own health. Good, green, ethical jobs. Childcare. A food system that is local and seasonal. Clean streets. Well-funded arts and culture. These things are not, really, a lot to ask for.

Not giving us this is a political choice, not an economic necessity. Giving us nothing is something they’ve chosen and continue to choose. And every time they say there is no money, they lie.

And if you have 50 minutes to try to better understand all this, here is a great place to start.

Get mad.

Excellent explanation of British economics,

I didn't expect too much of the new Labour government, but I didn't expect to be so totally disillusioned so quickly

You did a better job at getting me to understand British economics than any economist or politician I’ve listened to. Well done Heather, this must have taken hours to research and write. But also, I don’t know whether to laugh or cry at how bleak things are for us!